established MDCCCLVI

Untold stories of how M&T Bank conquered American finance

Charles Wilmers was the youngest of four children and his mother’s favorite. He was born in London, on January 6, 1909, to German-Jewish parents who immigrated to England in the 1870s (his father) and around the turn of the century (his mother).

After attending the University of Cambridge, Wilmers moved to Brussels, Belgium, in 1930, where he got a job at the largest utilities holding company in Europe, Société Financière de Transports et d'Entreprises Industrielles, or Sofina, which had properties in Belgium, France, Portugal, Germany, Turkey, Argentina, Spain and Mexico.

Sofina wasn’t an ordinary utilities company. It was more like a private equity firm that invested in the utilities sector. It accumulated stock in a company, agitated for a seat on its board, then consulted with the company’s management to improve operations.

This is what brought Wilmers to the United States in 1935. He had convinced his boss, Dannie Heineman, the chairman of Sofina, who built the company from four employees to forty thousand and by every account possessed a sagacious mind for business, that now was the time, with the economy gnashed in the teeth of the Great Depression, to scout investments in America.

“Mr. Heineman is a suave, quiet Belgian whose extreme shrewdness has given him the reputation of being the cleverest bargain hunter among European financiers,” reads a newspaper report from December 2, 1937. “While American utilities executives are twittering with fear for the future, the shrewd Mr. Heineman seems to have concluded that the business has hit bottom in this country.”

At Wilmers’ urging, Sofina settled on a company in Chicago that ranked among the largest utilities in the country, acquiring 3.4 percent of its outstanding shares by the end of 1937. “Oddly enough,” observed the same newspaper report, “the stock was picked up at a bargain rate from the Reconstruction Finance Corp.”

After living in Chicago for two years overseeing Sofina’s investment in the Middle West Corp., Wilmers moved to NewYork City in 1939 to help manage Sofina’s broader operations, which had been relocated to the city on the eve of World War II.

(Under the German occupation of Belgium, Sofina was declared a “Jewish company,” on account of Heineman and perhaps Wilmers as well, and thus subject to confiscation.) Wilmers later returned to Brussels in 1947, was named chairman of Sofina in 1955, and retired four years later at the age of 50. He then moved to Geneva, Switzerland, and made a fortune in the stock market.

“A tall, good-looking Englishman with a lordly air and raffish glint in his eye,” observed the esteemed chronicler of American business, John Brooks, in an article in The NewYorker about Wilmers’ ill-fated skirmish with a benefactor of the Spanish dictator, General Francisco Franco. “He was calm and unassailable and seemingly suave,” wrote Wilmers’ daughter, Mary Kay Wilmers, in The Eitingons: A Twentieth-Century Story, a book about her mother’s illustrious family.

Wilmers didn’t appear in the press again until seven years after his retirement, and then only tangentially. On January 15, 1966, it was reported that Jacqueline Kennedy and her two children, Caroline and John, had arrived via helicopter in Gstaad, Switzerland, to spend three weeks at Wilmers’ 10-room chalet, inclusive of maid and butler.

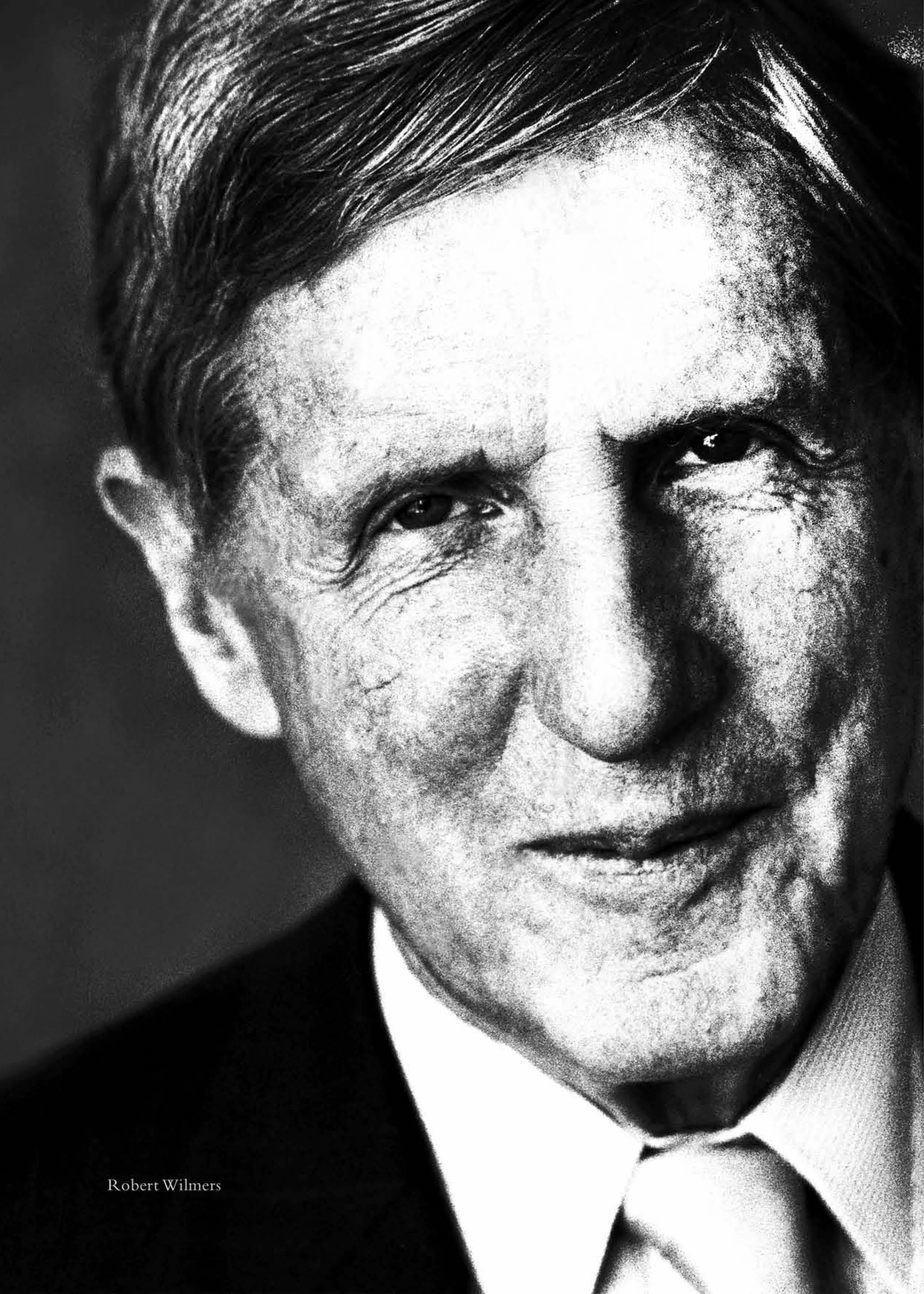

For years I’ve wondered where Robert Wilmers, Charles Wilmers’ son, acquired the sophistication, temperament and discipline to transform M&T Bank Corp. from an ailing, modestly sized bank in Buffalo, New York, into one of the most successful and celebrated financial institutions in America.

Here was the answer, I thought. It was in his blood. Transmitted from father to son. Or so it seemed...

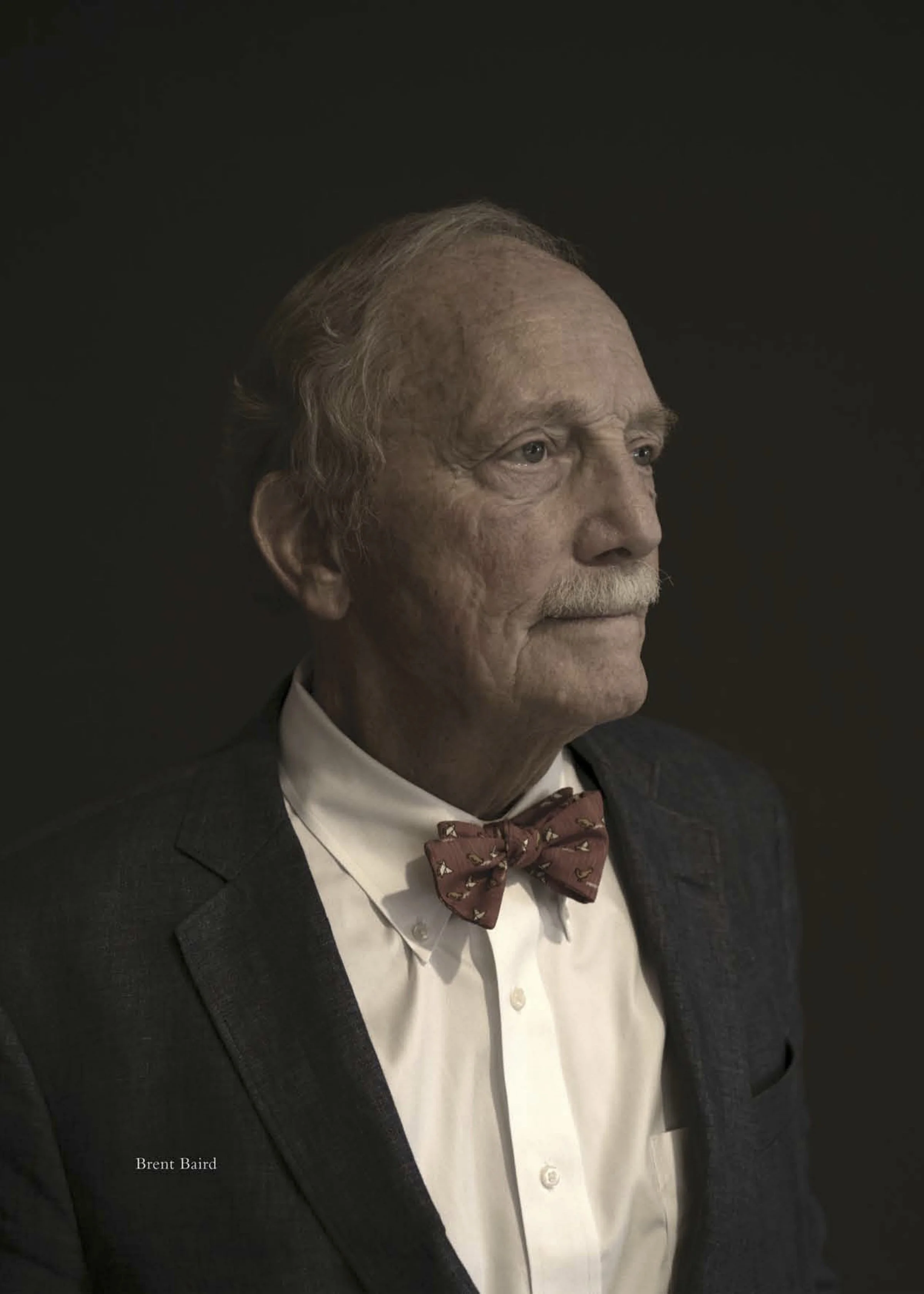

On May 27, 1980, while sitting in his office at One M&T Plaza, Brent Baird composed a letter to Robert Wilmers.

“Dear Mr.Wilmers,” wrote Baird, a partner in Trubee, Collins & Co., a brokerage firm based in Buffalo. “I have read Schedule 13D as filed by you and others on May 9, 1980. The clients of Trubee, Collins collectively own substantial amounts of First Empire shares, and it might be beneficial for us to discuss matters of mutual interest concerning First Empire. I am in NewYork City frequently and would enjoy meeting you at some convenient time. SincerelyYours, Brent D. Baird”

The Schedule 13D filed by Wilmers disclosed that he and a trio of affiliated investors had purchased 273,422 shares of First Empire State Corp., as the holding company of M&T Bank was known at the time. That amounted to 9.7 percent of its outstanding stock. The group included a wealthy Portuguese banker, a Swiss businessman and an investment entity owned by Cecilia Wilmers–Robert Wilmers’ mother and Charles Wilmers’ soon-to-be widow.

Baird had been involved before in fights for control of companies. “This could be fun,” he thought, “and it's right here in my hometown.” The fight was also personal for Baird, as his family owned 2 percent of First Empire’s outstanding shares and had become disillusioned with management after the bank’s dividend was suspended in 1976.

The Bairds are among Buffalo’s most prominent families. Baird’s grandfather, Frank Baird, was one of the city’s early industrialists.

He moved to Buffalo from Zanesville, Ohio, in 1888 and organized a series of iron and steel companies which he then sold, in 1922, to a larger concern, which itself was later acquired by an even larger concern.

“He was instrumental in the development of every blast furnace in the Buffalo district,” reads a 1939 obituary of Baird’s grandfather, referring to the recently deceased 86-year-old as a “leader in the city’s growth,” “Buffalo’s first citizen,” and the “father of the Peace Bridge” connecting Canada and the United States. The elder Baird had played an important role in M&T’s history too, serving on its board of directors from 1918 until 1937, when he was succeeded by his son, William Baird, Brent Baird’s uncle, who would occupy the seat for the next forty years.

If Wilmers was looking for hometown credibility, in other words, the Bairds would be powerful allies.

“Next time you're in NewYork City,”Wilmers told Baird on a call soon after receiving his letter,“let's get together.”

No institution that’s existed for 165 years has escaped the ebb and flow of fortune–M&T included.

M&T was established for the specific purpose of making credit available to Buffalo’s then-nascent manufacturing community. And that’s exactly what it did for the first seven decades after opening its doors on August 29, 1856. It took seven years for M&T to pass $1 million in assets. Fifty-four years to pass $10 million. And seventy years to eclipse $100 million.

Despite its slow but steady growth, M&T was already considered one of Western New York’s leading financial institutions by the turn of the century. “The Manufacturers and Traders Bank is one of the pillars of this community, a stronghold of the Greater Buffalo,” opined a full-page article from the May 13, 1900, edition of The Illustrated Buffalo Express. The article lauded the opening of M&T’s new office in downtown Buffalo, with “Established MDCCCLVI” etched into the frieze atop the three-story granite building.

The pace of M&T’s growth hastened after 1925. The American economy was still weening itself from the commercial bonanza of World War I. Drought and depression had settled over rural America. And in cities like Buffalo, a frenzy of mergers and acquisitions was sweeping across the banking industry.

It was within this vortex that M&T alighted on a period of rapid expansion, propelled by its 36-year-old president Lewis Harriman.

It’s been said that Harriman was a financial prodigy. He began his career with a prominent bond and investment house in NewYork City before graduating to the bond department at Guaranty Trust Co. On the side, he lectured on investments, railroad bonds and the trust business as a faculty member at New York University.

Harriman moved to Buffalo in 1919, recruited at age 30 to serve as vice president of the Fidelity Trust Co., which sat across the street from M&T and was controlled by a common nucleus of local investors. Five years later, in 1924, he was elected president of Fidelity Trust. And one year after that, he spearheaded a syndicate of Buffalo business moguls, including Frank Baird, to defeat an attempted takeover of both M&T and Fidelity Trust by outside interests. The attempt was rebuffed, the two institutions merged into one, and Harriman was elected president of the combined company.

Under Harriman, M&T would complete dozens of mergers over the next four decades and grow from $64 million in assets in 1925 to $722 million by the time he retired in 1964. But it was at that point that M&T’s fortunes took a turn for the worse.

In 1969, under new leadership and a freshly formed one-bank holding company, First Empire State Corp., M&T began a spurt of indiscriminate expansion. It acquired an international bank with offices in Paris and NewYork City. It chartered a bank on the island of Curacao in the Netherlands Antilles to serve the Caribbean and Central and South America. It established subsidiaries in Toronto to finance Canadian real estate. And it formed a joint venture, First Empire Realty Credit Corp., with a commercial real estate firm whereby the firm sourced and managed commercial development projects while M&T provided the financing.

First Empire loaned money to the Republic of Nicaragua for livestock development, to the Republic of Panama to modernize the public transportation systems in Panama City and Colón, and to developers of a 500-room Sheraton Hotel in downtown Indianapolis as well as a 131-acre condominium community in St. Petersburg, Florida, among others. By the end of 1973, at which point First Empire had grown to $1.9 billion in assets, it boasted a $100 million portfolio of international loans.

“The character of First Empire has changed considerably in the last year,” wrote First Empire’s chief executive officer, Charles Diebold, in the bank’s 1972 annual report. But any celebration would prove to be premature. After M&T’s earnings peaked in 1972 at $7.9 million, they declined in each of the next four years, culminating in a $2.7 million loss in 1976 that was fueled by a $5.6 million loan loss provision in its real estate joint venture.

M&T had reached the nadir of its narrative. It laid off employees, cut its dividend in 1975 and omitted it entirely the next year. It was only the second time that M&T hadn’t paid a dividend since its founding 120 years earlier, the first time being in 1886. Shares of the bank, which had been selling for $30 in the early 1960s, fell to around $5 in the wake of the announcement, recalls Brent Baird, whose uncle resigned from the board the following year.

At the bank’s annual meeting in 1977, shareholders demanded that executives take a 25 percent pay cut to “share the misery of the stockholders.” Its president, Claude Shuchter, responded by saying that he and his wife thought his salary was already “very low.”

Conspicuously absent from reports of the meeting was Diebold, the bank’s chairman as well as the chief architect of its wayward turn, who had retired from active management the prior month. (Even when M&T wasn’t doing well, Diebold was known to be driven around town by a full-time chauffeur.)

It was an ignominious end to a brief but ignominious era–the one time that M&T strayed from the prudent and profitable philosophy it’s known for today. Yet, the period would also serve as a blessing in disguise, sowing the seeds for decades of unrivaled prosperity.

The story of Robert Wilmers has been told many times before, and yet it’s a story that’s truly never been told.

Wilmers’ obituary in The New York Times reports that he was born in New York City on April 20, 1934, to Charles Wilmers and the former Cecilia Eitingon. But that’s only partially true. The full truth is that he was born to Cecilia Eitingon and her first husband–a fellow Eitingon, her cousin.

The Eitingons are a Russian-Jewish family that hails from a trio of villages along the Dnieper River in today’s Eastern Belarus. Arranged marriages among cousins were common in the Eitingon family; one of Cecilia’s aunts as well as one of her uncles had both married first cousins. But in Cecilia’s case it didn’t work out. The union, commemorated in Berlin in 1928, lasted just long enough to produce a son, Robert Wilmers (né Eitingon). Soon after her son was born, Cecilia, then living in New York City, divorced her husband and embarked on a European trip with her favorite uncle and family patriarch, Motty Eitingon. It was on the return voyage, in December 1935, aboard Cunard’s most luxurious transatlantic steam liner, the Aquitania, that Cecilia met Charles Wilmers, who was traveling to the United States to reconnoiter investments for his employer, Sofina.

Charles and Cecilia married in London on June 15, 1937, spent their honeymoon in Switzerland, then returned to the United States, where they lived for the next two years in Chicago while Charles oversaw Sofina’s investment in the Middle West Corp. (It was in Chicago that Robert Wilmers’ half-sister, Mary Kay, was born.) The foursome moved to New York City in 1939 before embarking across the Atlantic to Brussels in 1947, after the war had concluded, as Charles climbed Sofina’s corporate ladder.

In New York, Wilmers and his sister were surrounded by Eitingons, proprietors of the world’s largest fur dying and trading business. Wilmers spent many a day at his Great-Uncle Motty’s estate on Long Island, his sister recounts in her book on the Eitingons. In Europe, their family traveled in chauffeured cars and spent holidays in Switzerland. Their father rubbed shoulders with royalty and heads of state, crossed swords with obstinate dictators, named the former governor of Belgium’s central bank to be his successor, and would later host the widow of an American president at his Swiss chalet.

Wilmers attended the elite Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire for high school, graduated from Harvard University in 1956 with a degree in modern European history, and spent a year at Harvard’s Graduate School of Business Administration. In 1962, he started work at Bankers Trust Co. in New York City, specializing in overseas debt and equity financing. Four years later, he joined the administration of NewYork City Mayor John Lindsay, overseeing 2,000 people and a $6 billion budget. He then returned to banking in 1970 to run the Brussels office for Morgan Guaranty Trust Co., moving back to New York City later that decade to head its international banking division.

In 1979, on the eve of his adopted father’s death the following year, Wilmers resigned from Morgan Guaranty and formed a private partnership to invest in banks. He drafted a list of 80 or so potential banks with between $1 billion and $3 billion in assets in which to acquire a controlling stake. Then he narrowed the list down to two: Union Commerce Corp., a $1.5 billion bank based in Cleveland, Ohio, and M&T, with $1.8 billion in assets. Both had fallen on hard times and were selling for steep discounts to book value. Both could be accessed by short, direct flights from NewYork City as well, a not-insignificant condition. Wilmers also happened to frequently bike past M&T’s sole New York City location on the corner of 60th Street and Madison Avenue on his way to work.

But Union Commerce was already the target of an ongoing hostile takeover attempt. (It would be subsumed, in 1982, into Columbus, Ohio-based Huntington Bancshares.) That left M&T as the sole bank in Wilmers’ crosshairs.

By May 19, 1983, the coup was complete.The investor group led by Robert Wilmers had amassed a third of M&T’s outstanding stock over the previous two and a half years, much of which was purchased for $21 per share, roughly half the bank’s per-share book value, in a private transaction on March 2, 1982. It wasn’t an outright majority, but it was enough to secure control of a company like M&T with a large and dispersed shareholder base.

Wilmers joined M&T’s board in April 1982 (as did Jorge Pereira, the Portuguese banker who had been acquiring stock in unison with Wilmers), became president later that year, and at the bank’s annual meeting in May 1983 was elected chairman and chief executive officer. (Brent Baird joined the board in 1983 as well. He was the third generation of his family to do so, ultimately spanning nearly a century.) On most Monday mornings for the next thirty-five years,Wilmers flew from New York City to Buffalo, where he maintained a pied-à-terre in an elegant high-rise on the fringe of the Elmwood Village neighborhood, and then returned home to his Central Park West apartment in New York City most Wednesday evenings.

The first order of business for Wilmers was to recruit talent. “Bob looked at us when he got here and almost everyone, if they'd gone to college, had gone to school in town, at either Canisius College or University of Buffalo,” recalls Shelley Drake, the long-time head of M&T’s charitable foundation who grew up in Buffalo, joined the bank in 1971 and recently retired after fifty years. “The business community was nervous when he started bringing all these people in from New York City. Extremely nervous. They were sure he was just going to grow the bank, sell it and get out of here, which, of course, is exactly the opposite of what happened.”

Wilmers then set about purging M&T’s balance sheet of dubious loans, introducing previously shunned products like consumer mortgages, and jettisoning the international banking aspirations of his immediate predecessors. It was only after all of this was done that Wilmers, in what would prove to be exquisite timing, turned to his attention to growth.

Since the earliest days of the United States, most states forbade banks from operating branches or conducting traditional banking business over interstate lines. It wasn’t until the 1950s, when Wilmers was at Harvard, that the political aversion to big banks started to thaw. In 1960, the state of New York began permitting the creation of bank holding companies, which had been barred since the mid-1930s. By 1976, New York banks could establish offices statewide. Nine years later, in 1985, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the power of states to enter interstate banking compacts with their neighbors. And nine years after that, Congress removed what remained of the federal restrictions on branch and interstate banking.

A new era in American banking had dawned. It was an era of consolidation, one in which the population of commercial banks in the United States would decline from a peak of 14,496 in 1984 to less than 5,000 by the end of 2017. Unit banks became community banks. Community banks became regional banks. Regional banks became national banks. In 1984, not a single bank held more than $250 billion in assets. By the end of 2017, there were nine, holding half of all assets in the industry.

Even among the period’s most active and celebrated acquirers–Hugh McColl at Bank of America, Dick Kovacevich at Wells Fargo, the Grundhofer brothers at U.S. Bancorp–Wilmers and M&T stood out.This wasn’t because M&T grew faster than any other bank during his tenure, because it didn’t. It was rather because M&T mastered the uniquely delicate balance that exists in banking between growth and value creation.

From 1983 to 2017, M&T completed nearly two dozen acquisitions and grew from $2 billion to $119 billion in assets, transforming from the fourth largest depository institution in Buffalo to one of the biggest financial institutions in America. And along the way, it created more value for shareholders than any other publicly traded bank in the country. “Of the 100 largest banks in 1983,” notes an M&T presentation from just before Wilmers passed away on December 16, 2017, “only 23 remain.” Among those, M&T ranked first in terms of both stock price growth and total shareholder return.

The first time I interviewed René Jones, we were in Robert Wilmers’ former office on the nineteenth floor of One M&T Plaza in downtown Buffalo. It was August 23, 2018, eight months and one week since Wilmers passed away and Jones was named chairman and chief executive officer of M&T.

The whole floor was an exhibit of elegance. High ceilings. Teak paneling. Private bathrooms. Luxurious silence. A specimen from the halcyon times of American high finance.

Wilmers’ colossal, oblong office occupied the southwest quadrant of the floor. On one side sat his desk, situated so Wilmers’ back was to the windows pointing south. He faced this way, it’s said, though perhaps not entirely seriously, to avoid gazing all day at Buffalo’s tallest building, which was crowned with the logo of the city’s oldest and biggest bank, the once mighty but long since squandered Marine Midland Corp. On the other side of the room was a seating area with a couch and four chairs spaced precisely and geometrically around a large, square coffee table.

Everything was left as it had been eight months and one week before. It didn’t feel right to move into Wilmers’ office, said Jones. They were rethinking the floor.They wanted to modernize it, temper the extravagant trappings, narrow the chasm between the occupants of the nineteenth floor and everyone else.

It’s critical to appreciate that Jones is one of just four Black CEOs in the Fortune 500. He and his four siblings, whose complexions, as he likes to say, span the width of the white-to-black spectrum, were born to a mixed-race marriage. His father was Black, the thirteenth of thirteen children who grew up on a farm in rural Virginia. His mother was white, raised in a small village near Liege, Belgium. They met in December 1944, as his father was marching in formation through her town with General Patton’s Third Army toward the Ardennes Forest to repel Germany’s last, desperate counteroffensive of World War II, the Battle of the Bulge.

Meeting Jones for the first time is like reuniting with an old friend. He radiates familiarity.The angle and distance at which he stands from you. The easy and unhurried way he engages in conversation. His use of humor and eye contact. He possesses the rare ability to put one at immediate ease. Of all Jones’ traits, however, the most pronounced is his quiet, philosophical demeanor. He spends 40 percent of his energy trying to stay calm, he once remarked. If that exceeds 50 percent, he continued, it defeats the point.

When asked to describe his father, Jones tells a story about hunting near their home in Ayer, Massachusetts. “We would be walking with our shotguns slung over our shoulders and would get to a place where we'd have to cross a large field that was owned by a farmer who didn't want anybody to trespass,” recalls Jones. “My dad would say, ‘Okay, we're going to go over to the other side, and when the farmer comes on his tractor, I want you to keep walking and look straight ahead. No matter what he does, don't say a word, just get to your destination.’”

That’s how Jones communicates. He tells a story about hunting, which seconds as a parable about banking. Banking at its most fundamental level is a business of temperament, discipline and intellectual independence. It’s about keeping one’s head, to paraphrase Kipling, when everyone else is losing theirs. It’s about possessing the confidence and wherewithal to combat Warren Buffett’s institutional imperative: the tendency of bank executives to mindlessly imitate the behavior of their peers no matter how foolish it may be to do so.

That was Robert Wilmers’ greatest strength. And the same is true of Jones, who possesses one of the sharpest philosophies and most forward-thinking strategic perspectives in banking.

Three years after interviewing Jones for the first time in Buffalo, we spoke again, on August 5, 2021, in the recently renovated executive suite at One M&T Plaza. We were in the chairman’s lounge, the truncated remainder of Wilmers’ office, the lions’ share of which had been repurposed into a new boardroom. The same coffee table was there, as was one of Wilmers’ sharpened No. 2 pencils resting on an end table. A couch and four chairs were, as before, situated precisely and geometrically around the large, square table.

Afterwards, we walked up to Jones’ new office on the twentieth floor. It’s encased in glass, not teak. There’s a desk. Two chairs. A credenza. No high ceilings. No private bathroom. No palatial suite. Not even a sign on the door designating it as his office. It’s nice, but also ordinary. If it weren’t on the twentieth floor in the corner, with a modest, adjacent sitting room, one would think it’s inhabited by a mid-level vice president, not the chairman and chief executive officer of a soon-to-be $200 billion bank.

“René's passionate about breaking down hierarchies,” says Rich Gold, M&T’s president and chief operating officer. “We want to make sure that we always remain approachable, that we’re viewed as regular people, that people understand that we're just playing our roles in the organization like everyone else is playing theirs.”

If you ask Rich Gold and Kevin Pearson, the two executives in addition to René Jones who occupy M&T’s office of the chairman, to explain the bank’s success over the past forty years, they say the same thing but get there in different ways.

Gold traces M&T’s success in part to a pair of local savings and loan institutions that collapsed in 1990 and 1991. Empire of America, which occupied a 26-story tower directly across the street from One M&T Plaza, was the twelfth largest depository institution in the United States when it failed in 1990. Goldome, the country’s thirteenth largest depository institution, residing four blocks to the north of M&T’s headquarters, was seized by regulators the following year. (M&T partnered with Key Bank to assume the deposits of both institutions, and in the process of doing so recruited Warren Buffett as an investor.)

“You came out of your front door one day to get the newspaper, looked to your left and your right, and there was a good chance that one of your neighbors was out of work,” recalls Gold.“That drove our employees to say, ‘That isn’t happening to us.’ People were willing to walk through walls for this organization because the opposite of that was just untenable. It also bred empathy that we carried into every one of the deals that we completed over the next thirty years.”

The experience had a similar effect on customers throughout Western New York, where M&T holds 63 percent of the region’s deposits. “People saw that we're not going to pull up stakes when things get bad,” says Gold. “That stability and understanding of our commitment to a community, whose health and vitality rubs off on the success of our borrowers, allows us to see most opportunities that present themselves in our markets, allows those opportunities to accrue to us, and probably enables us to charge a little bit more.”

Indeed, far from being a hinderance to its success, M&T’s roots in Buffalo, a city that has seen more than half its population flee since the late 1950s, is one of the bank’s most exportable assets. It underlies the success twenty-two years later of M&T’s acquisition of Allfirst Financial, the biggest bank based in Maryland, with headquarters in Baltimore, a city on a similar demographic trajectory to Buffalo. And the same is likely to unfold with M&T’s latest acquisition, announced on February 22, 2021, of People’s United Financial, the biggest bank based in Connecticut.

Gold’s perspective is shared by Pearson, though the 60-year-old vice chairman of M&T comes at it from a unique vantage point.

Pearson grew up in Morgan Hill, California, an hour south of San Francisco. His father was a second-generation homebuilder, who had acquired 300 acres in 1973 and the rights to subdivide and develop the property into single-family homes. Halfway through doing so, in 1977, Morgan Hill capped the number of new homes that could be built each year. The initiative dramatically increased the value of Pearson’s father’s remaining undeveloped lots, which he sold in 1979. His father then retired at age 50, bought a 53-foot Hatteras and spent the next decade sailing with Pearson’s mother up and down the West Coast.

All of this is to say that the Pearsons were well-established, respected members of their community. An all-American family. So it came as a shock when their son, who was captain of his high school football team and later moved to New York City in the mid-1980s after finishing graduate school and getting a job at Citibank, called to say that he was gay. “They struggled from the standpoint of how their friends would react,” says Pearson. “That's the generation they were in. There was no religious problem. The issue was, ‘How will this be interpreted by the world?’” Over the next two decades, Pearson and his parents intermittently went years without speaking.

It wasn’t until long after Pearson joined M&T in 1989 that his parents came around. The birth eleven years ago of Pearson and his partner’s first child, Pearson’s biological son who was born via surrogacy, marked the turning point for Pearson’s mother. The final turning point for his father came soon after, when Pearson introduced him to Robert Wilmers, whose office in New York City, where Wilmers worked most Thursdays and Fridays, was next door to Pearson. “I could see my father beginning to realize, ‘Holy cow! My son has this enormous office on Park Avenue right next to Bob Wilmers, the iconic banker,’” recalls Pearson.

Pearson cites the aura around this experience when explaining what makes M&T unique.“Coming out is an incredibly personal thing,”he says.“And having lived through that at the bank and still gotten promoted afterwards speaks to what BobWilmers started here 40 years ago.”

It’s about empathy and support for communities, explains Pearson. Not in the superficial way that every executive at every organization robotically rattles off the buzzwords that are so in vogue at the moment. But in a substantive, genuine way. One needn’t look further than downtown Buffalo, where M&T has poured millions of dollars into a new technology hub that’s designed not just to bring together the bank’s digital talent, but also to create a positive halo effect for the broader community. And the same is true throughout the organization, which has announced in recent years the appointment of Glenn Jackson as chief diversity officer and Aarthi Murali as chief customer experience officer.

“This city has a narrative to tell about attracting talent, not just in technology, but creative talent, business talent,” M&T’s executive vice president in charge of consumer banking, business banking and marketing, Chris Kay, explained to Matt Glynn of The Buffalo News soon after joining the bank. “I'm excited as we look to continuing to grow our teams, that others will look at Buffalo differently.”

The most innocuous details can sometimes belie the most extraordinary insights. Such is the case with M&T’s 1994 proxy statement, an otherwise tedious document that discloses, among other things, the identity of the bank’s largest shareholders.

All the usual suspects are present. There’s Warren Buffett, who controlled $40 million worth of M&T’s preferred stock, which would later convert into common stock. There’s Brent Baird, the prominent Buffalonian and early Wilmers ally, who represented a group that held 6.2 percent of M&T’s outstanding shares. There’s Jorge Pereira, the Portuguese banker and friend of Wilmers from their time together in Europe, who accounted for 6.1 percent of M&T’s stock. And there’s Wilmers himself, who owned 9.2 percent of M&T’s shares in his own name, making him the bank’s largest shareholder.

And then there’s the Rem Foundation. It owned 451,320 shares, or 6.6 percent, of M&T’s stock, second only to Wilmers. The document offers few clues as to the identity of the Rem Foundation’s beneficiaries. The answer lies instead in a Schedule 13D filed the following year. “Rem Foundation's principal business is making investments in, and holding securities of, other businesses,” the form discloses. Among the beneficiaries is Mary Katherine Frears [aka Mary Kay Wilmers] the sister of Robert G.Wilmers.

In 1980, the same year that Charles Wilmers passed away and Robert Wilmers used a portion of his father’s fortune to begin accumulating shares of M&T, Mary Kay acquired the London Review of Books, which she would edit for the next four decades. Since then, despite being one of the world’s most prestigious literary journals, the publication has lost an average of $1 million a year.

“Where does all the wealth come from?” a reporter from The FinancialTimes opined in 2015. “Her father worked for a utility company and so … is unlikely to have earned enough to support his daughter’s literary magazine in perpetuity.”

“He made … investments,” Mary Kay told the reporter. “I’m really going to get into trouble. Let’s just say, I owe a lot to my brother.”

In Mary Kay’s book about her mother’s family, she talks about her favorite great-uncle, Motty Eitingon, the patriarch of the Eitingon family, the one who accompanied her mother on the European trip in 1935 during which Mary Kay’s parents met, the great-uncle whom her half-brother Robert Wilmers spent so much time with growing up.

“He gave money to art and to artists but in his heyday he also supported most of the extensive Eitingon clan,” Mary Kay wrote about Motty. “That’s how it is,” Mary Kay’s mother explained in a letter to Charles Wilmers a few months before their marriage in 1937, “everyone in the family participates.”

At long last, it struck me, herein lies the final stanza in the story of how M&T Bank conquered American finance.

It isn’t just a story about a bank, I realized. It’s a story about one’s duty to family. It’s a story about doing what’s right, even if it isn’t popular. It’s a story about effort over neglect in cities like Buffalo, New York, that so many others have left for dead. But most importantly, it’s a story about courage and resilience.

Had the Eitingons not fled Eastern Europe before the Nazis rounded up and annihilated an estimated 90 percent of the remaining Jewish population of Belarus; had Charles Wilmers and his boss, Dannie Heineman, both of German-Jewish descent, remained in Brussels during World War II instead of coming to America; had soldiers like René Jones’ father not marched through a small Belgium village in December 1944 to pound the final nail in the Nazi’s coffin; this would be a story of tragedy, not triumph.

But light prevailed over darkness. That’s the story of M&T Bank.

as seen in print buy the issue or full article