hands on

In the OR, identity emerges at the head or the feet. Surgeons, fellows, residents, interns, touring first-years, anesthetists, surgical nurses–even guests like me–all wear the same essential costume. Sky-blue scrubs, hair nets, face masks. For anyone with hands on the patient or the instruments, double-layered nitrile gloves, clasped at chest-height or hovering between the shoulders and the waist. From the eyeballs to the ankles, there is surprisingly little variation across the OR’s complex hierarchy; and every article of clothing sends a simple signal about one’s relationship to the patient. But you can say a lot about yourself with a hair net. Like the nurse who ditches the standard elastic gauze for a sturdy cotton wrap, printed with playful sea otters. Or the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery team, attending surgeon Dr. Michael Markiewicz and his residents, clad in flat-topped black UB OMFS caps like sushi chefs. And here, all shoes are statement shoes–from the workhorse Hokas and Sketchers to the anesthesiologist’s decorated Crocs, the attending surgeon’s dainty clogs, and the fellow’s cracked brown cowboy boots, which indicate both that he trained as a resident in Texas and that he wasn’t prepared with balsam and conditioner for Buffalo winters.

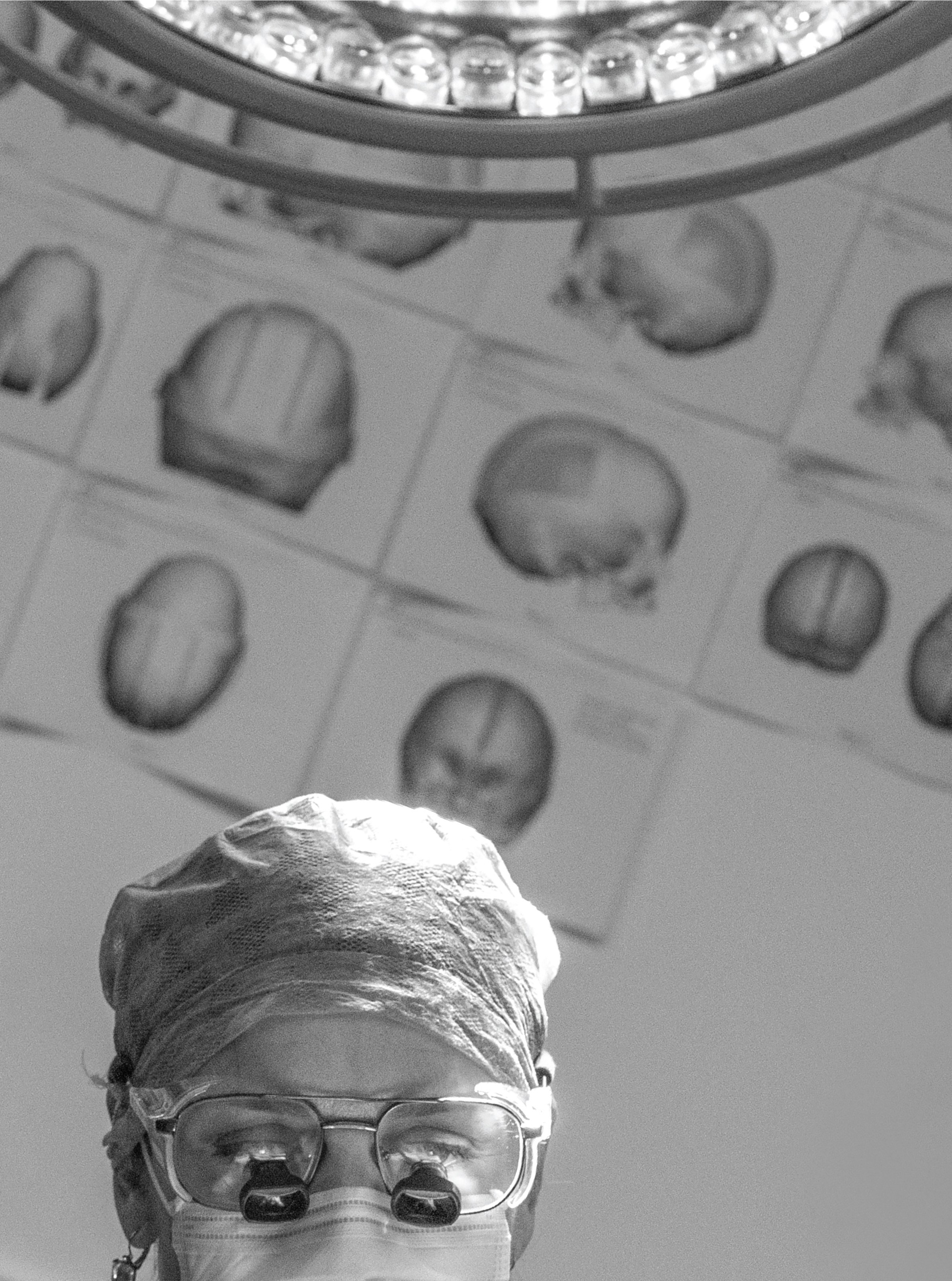

Except for Dr. Renée Reynolds, the attending neurosurgeon this morning at John R. Oishei Children’s Hospital in Buffalo, New York. She wears the same costume as the rest of us. But her presence seems to proceed her, like an invisible courier, running ahead and announcing her before she enters a room. Residents rubberneck as she enters the elevator. Second-years press against the wall of the Pediatric Neurosurgery wing as we pass. Dr. Markewicz, walking with purpose and flanked by fellows, stops in his tracks to share just a few words with Dr. Reynolds, log-jamming the hallway. And when Dr. Reynolds pushes open the doors of the OR–where the two-year-old patient is already stripped and prone on the operating table, the urgent abnormality of the skull immediately apparent–she is like a new planet appearing in a solar system, changing the gravity of the place, and subtly altering the orbits of everything else that moves.

Bodies exchange across the threshold of the elevator. Some in white coats, some in blouses and button-ups, some in street clothes. People busy getting where they’re going. Except one. She takes only two certain steps into the hallway before stopping, becoming the only fixed point in the Friday morning traffic.

“What are you looking for?” Dr. Reynolds says from the elevator, breaking off our conversation. The woman turns, adjusting a large shoulder bag, the kind that can hold multiple water bottles, paperbacks, an iPad, extra masks, snacks, official forms, and brochures–the kind popular with the keepers of hospital vigils.

The elevator doors close with unnatural speed. Dr. Reynolds throws her right hand into the gap, and for half a second it looks like the doors are determined to meet in the middle, indifferent to the surgeon’s fingers. They release her reluctantly.

“Make a right and a left, second building on your left,” she says. The doors try a second time, and soon we’re rising.

“I guess I should be more careful,” Dr. Reynolds says, flashing her open fingers between us. “These are my livelihood.”

Our conversation picks up roughly where we left it. Somewhere below us, a woman is arriving where she’s needed. I get the sense this wasn’t the first time Dr. Reynolds has jammed her fingers in an elevator door–and it won’t be the last.

Dr. Reynolds fills a vacuum. In many cases it is a vacuum that goes unrecognized until she appears.

Growing up, Renée was one of three. She was more of a mother-figure than a sister to her younger brothers, she says–eight and eleven years behind her.

Today, Dr. Reynolds is one of 219. That’s the number of women certified by the American Board of Neurological Surgery–fewer than the Spartans at Thermopylae, representing just over six percent of the 3,600 board-certified neurosurgeons in the U.S. “It’s getting better,” Dr. Reynolds says–women make up 12 percent of the neurosurgeons currently in training. But as other areas of medicine approach parity–with roughly 49 percent of new white coats going to women–the field of neurosurgery stands out.

We meet for coffee in Dr. Reynolds’s office in the Conventus building on the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus a week before the surgery–a craniotomy and insertion of cranial distractors in a child afflicted with craniosynostosis, an early fusing of the plates of the infant skull. Trapped in a misshapen container, the brain’s massive growth in a child’s first five years can result in elongated skulls, severe developmental delays, and vision problems–even total blindness.

The condition is rare, but this will be a standard procedure for Dr. Reynolds, one of only two pediatric neurosurgeons in Western New York. Sitting at her desk, beside a window facing the perpetual construction on Main Street, and in front of a standard medical office hutch holding pictures of her family, notes from colleagues, and a framed watercolor cross-section of the human brain, she ticks through the types of surgery her team typically handles: brain tumors, epilepsy, hydrocephalus, spasticity.

Dr. Reynolds isn’t only an attending surgeon; she’s also a clinical associate professor of neurosurgery at the University at Buffalo Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, and the director of its neurosurgical residency program.

She’s the Medical Director of Pediatric Neurosurgical Outreach and Education for Kaleida Health.

She’s a mother of five children.

And she has other roles that aren’t immediately clear: Only a few hours before, Dr. Reynolds was in Miami, interviewing another neurosurgeon–one of the 219, a “legend,” she says–for what I assume to be an industry publication.

Dr. Reynolds earned her MD at SUNY Upstate Medical University, did her neurosurgical residency at Duke, and completed a one-year fellowship in pediatric neurosurgery at Seattle Children’s Hospital at the University of Washington.

“I met a lot of resistance,” she tells me. “Not because they didn’t think I’d be capable. But because they were fearful of what my life would be like.”

Dr. Reynolds sketches out the typical paths of a career in neurosurgery.

Burn out and retire early, whether you love it or loathe it.

Become your work; practice until you collapse. (Dr. Reynolds cites her mentor, now 73 years old and still working four days a week.)

Find the middle ground, whether you enjoy it or not; retire at an appropriate time.

It’s too early to tell whether Dr. Reynolds will end up on the second or third path. But it’s clear that she loves her work–all of it.

Still, she is conscious of the risks. Burnout comes in several guises. Neurosurgeons have one of the highest divorce rates in medicine–and one of the highest multiple divorce rates, Dr. Reynolds says. There are smaller sacrifices, too. Did you see this thing on TV? Did you hear about that? How about the weather last weekend? None of Dr. Reynolds’s close friends are doctors, she says, and she doesn’t tend to discuss work once she leaves the medical campus. I get the sense that in her world, everyone outside work is always watching some show that she hasn’t seen–a shorthand for all the small things that neurosurgery takes from you.

“I’m happy with my lifestyle,” she says, trailing off before deciding to put a period at the end of the sentence. “Other people wouldn’t be.”

Late spring in Central Park. Leashed dogs, shirtless joggers, and two unicyclists pass beyond the fences. A peregrine falcon circles the North Meadow, surveying squirrels and sunbathers. Straight down Field 12’s foul line and above the trees soar the gray grilled flanks of Mount Sinai. Down here, in the orange dirt, 40 neurosurgeons grip bats, pound gloves, shout insult and encouragement.

Since 2003, Columbia University Medical School has hosted the country’s neurosurgical students and residents for an annual softball game to raise money for the Andrew T. Parsa fund for brain tumor research. Only bragging rights are at stake. But this is enough. The typical neurosurgical residency is seven years. There are few opportunities for exercise, let alone competition, amid 60-hour weeks, 24-hour call shifts, night floats, boards, and research for publication. But once a year, in Central Park, America’s next neurosurgeons and their mentors set aside all this to give vent to deep-running personal and institutional rivalries–for charity.

Buffalo cannot give up the title to Miami–not on a technical disqualification. The tournament is competitive, but there are a handful of dominant teams. Arizona’s Barrow has taken home the trophy–a mounted human skull, missing its top half, with a golden softball where the brains should be–more than any other team. But Miami has won twice, last in 2016. They’re hungry. In active training, they practice three nights a week. They have a professional batting coach. Buffalo has never won the title, though they’ve come close. This year–June 2022, the tournament returning after a COVID-imposed hiatus–Buffalo has pushed into the final four. A resident’s poorly timed bathroom break lands Dr. Reynolds where she hadn’t planned to be: behind home plate, wearing a face mask, a chest plate, and a catcher’s mitt.

Dr. Reynolds has been playing in the tournament since 2006, first with Duke. She loved the annual tradition but had hoped to semi-retire into a coaching position befitting her UB faculty status, letting the younger residents, some still in their twenties, take the field. But then there was an opening, an urgent need. She did what she has always known to do.

A runner on first, leading. Late in the fourth of five tournament innings. The Miami batter hits what for a moment looks like a single–no, a double–but then UB’s center fields the ball on the first bounce and lobs it to the shortstop–too high, the runner pushes for a triple, for a home run, almost lapping his teammate–and the shortstop, who played D1 hardball, sends a sidearm screamer to Dr. Reynolds.

OUT and OUT!

Ouch.

I think of the story–and of the image Dr. Reynolds pulled up on her cell phone, showing a broken right hand, swollen over the metacarpals, bone-bruised and almost black at the knuckles–as I watch her in the OR holding court over the unconscious body of the patient, preparations for surgery underway. Objects pass in and out of her hands; others seem to move around the room as if levitated at her direction: tape, padding, plastic sheets, floppy tubular blobs filled with liquid the color of apple juice. As Dr. Markiewicz shaves the patient’s head, making long, gentle strokes with an electric razor, Dr. Reynolds fills a space beside him, using surgical scissors to cut padding that a nurse will attach to the child’s face. Moments later, Dr. Reynolds is at my side, sending an email from her phone, explaining to me how she’ll update the patient’s parents after the surgery, and admitting to an orbiting resident that, yes, she was working from her laptop on a hotspot from the stands at her son’s baseball game last night.

What I mean is that Dr. Reynolds is everywhere at once, one being in several persons. If you are a surgeon, teacher, mentor, mother, friend, administrator, or charity softball sub you don’t get to stop being any of these things just because one or another, at this moment, has your attention. Dr. Reynolds’ many roles and roaming focus make this obvious.

She’s moved again–now with a half-moon of residents and medical students around her, all facing a wall tacked with CAD mock-ups of the patient’s irregular skull, clean-cut portions of bone highlighted in green and red seeming to float off like the doors of a McLaren.

“This was theoretical ten years ago,” she explains–a nod to the aggressive pace of innovation in the field of neurosurgery, a fledgling compared to orthopedics or general surgery, where some “best practices” date back two centuries. “We didn’t have this when I was a resident.”

What did we do?

“We took the whole skull off,” she explains, “broke it into pieces, and put it back together with plates.”

The procedure we’re attempting today is still maximally invasive. It involves cutting into the skull along the prematurely fused sutures and inserting mechanical cranks called distractors. These–which will poke out of the skull for a month or more–allow the parents to pry open the child’s skull from the comfort of their home, gradually, a quarter twist a day, giving the brain precious millimeters to adjust and develop. This is “a gamechanger,” Dr. Reynolds says.

Our pediatric patient is no Yorick, but I can’t miss the resemblance to Hamlet as Dr. Reynolds raises a transparent, 3D-printed skull and traces the fused coronal suture with an index finger. This level of pre-operative planning has also been a game-changer for the rapidly evolving field of neurosurgery. The team has mapped the patient and plotted each incision in three dimensions. A nurse uses calipers and gauze to paint the real patient’s hairless head with something that looks like viscous root beer and dries closer to the color of barbecue sauce. Behind her the attending surgeons–like choreographers–use the model to negotiate last-minute calibrations down to the millimeter.

And it is a dance, beginning sooner than I could have expected.

Dr. Markiewicz produces a JBL Bluetooth speaker and cues up an eclectic mix–90s hip-hop, Santana, some country. The cutting begins.

The scalp is blubbery. It’s like skinning a fish. When the chief resident stretches it back, the shape of his two gloved fingers clear through the taut pale underside, I can’t believe it doesn’t rip.

The maxillofacial team goes first, and Dr. Reynolds visibly struggles to wait her turn. She moves to raise the volume on the speaker–now playing DMX: Y’all gonna make me lose my mind (up in here, up in here).

Dr. Reynolds reappears beside the operating table as the residents and nurses fit a white mold to the child’s skull–which is now entirely exposed, the scalp stretched away and held in place with a half-dozen locking tongs and a few rubber bands. From the side, the skin bunched over the toddler’s ears resembles the multiplying folds of a pug. A transparent garbage bag below the head collects countless rivulets of bright blood. Above and around the body, the doctors and nurses chat about movies, kids, the politics of the hospital.

I know the bone when I smell it. The experience is without comparison. A resident wields the craniotome–a fine-tipped bone drill–while Dr. Reynolds works with another, apparently analog instrument. Safer for thinner portions of the undeveloped skull, this allows the surgeon to chip away without removing any of the delicate dura or tugging on the brain. The procedure requires cuts very close to the veins of the dura that draw all blood from the brain. An inadvertent impact to the brain itself could cause incalculable damage. An injury to the blood vessels of the dura, Dr. Reynolds explains, would result in “death on the table.”

There is an art to the way she works with the chipper, the tip slowly widening a hole little bigger than a ladybug. After this incredible display of delicacy, the smell of bone shocks me less than the appearance of a miniature crowbar, which Dr. Reynolds inserts into a new rift in the skull, still hot from drilling and chipping, and tilts, making enough room for Dr. Markiewicz to return and slip in the mechanical distractors. They fix them in place with screws they’ll remove later.

Television may have trained my pulse to rise in tandem with the tempo of machinery beeping in an operating room–but I know to pay attention when both surgeons are standing away from the patient and reexamining their 3D-printed skull. They tilt and spin, glance at the CAD mock-ups taped to the wall, and turn to compare these to the patient. New tech is accelerating neurosurgery–but the map will never be the territory.

“I think,” Dr. Reynolds says, calmly, “it goes here.” She points to the skull. “I drilled here.”

For a moment I imagine this procedure is like a rocket launch: any delay to recalibrate, consult calculations, could mean missing a narrow window. I imagine they’ll need to remove everything, put the scalp back on as quickly as possible, and reschedule a second surgery, say, two weeks out. But the fix is simple. Dr. Markiewicz and Dr. Reynolds take a crank, agree on a position, and screw it in.

This is more impressive than a wholly by-the-plan procedure would have been. It’s a reminder that behind the computer programs, advanced tools, and semi-autonomous systems, there are people–using creativity and some of our species’ oldest tools to solve infinitely permutating challenges. And it reminds me of something Dr. Reynolds had told the room during prep.

“I go on the Facebook page,” she said, referring to a private group for families of patients with craniosynostosis. There, parents, guardians, and other loved ones post photos of success stories and glowing, unprompted testimonials about apparent miracles. “I don’t comment, because, you know … But I see what they post. And you know what? We do a good job.”

This energy will carry the team into the afternoon. Anyone who had hands on the patient will have to “unscrub.” Dr. Reynolds will visit the parents–and then return to repeat a nearly identical surgery. Then a third, relatively simple operation on another patient before changing into street clothes and returning to her own family, who will be eager to talk about the adventures and setbacks of their own disparate days.

in print discover issue twenty four

In what feels like minutes, the stretched scalp is back in place, stapled around new titanium interruptions. Someone holds up a blue sheet as a backdrop while the chief maxillofacial resident snaps photos with a Nikon. Now, Dr. Reynolds is circling the OR, answering questions, gloved hands clasped and twitching to take up her phone, work through a growing pile of emails. I wonder if she’s silently composing the update she’ll deliver to the parents, who wait somewhere nearby. I imagine they aren’t interested in the play-by-play I just witnessed; their minds have been fixed for two years on a future that keeps receding into uncertainty. Is our baby okay? What’s next?

Any doctor knows that answering questions like these is an exercise in gestures, in probabilities. Certainties are few–this is evident every minute in the OR. But as I change back into street clothes, step back out into our slower, lower-stakes world, I know this: Anything can come apart. Almost everything can come back together again.