lloyd cole in conversation

As soon as Lloyd Cole steps out of the busy coffee shop’s front doors he hooks a right and pours half of his 24 oz. “mucho” breakfast tea into the garbage can. There’s something about the impropriety of the obvious waste that makes him twinge, but not as much the size of the tea itself. “It’s frankly offensive to an Englishman that tea could be this big,” he says.

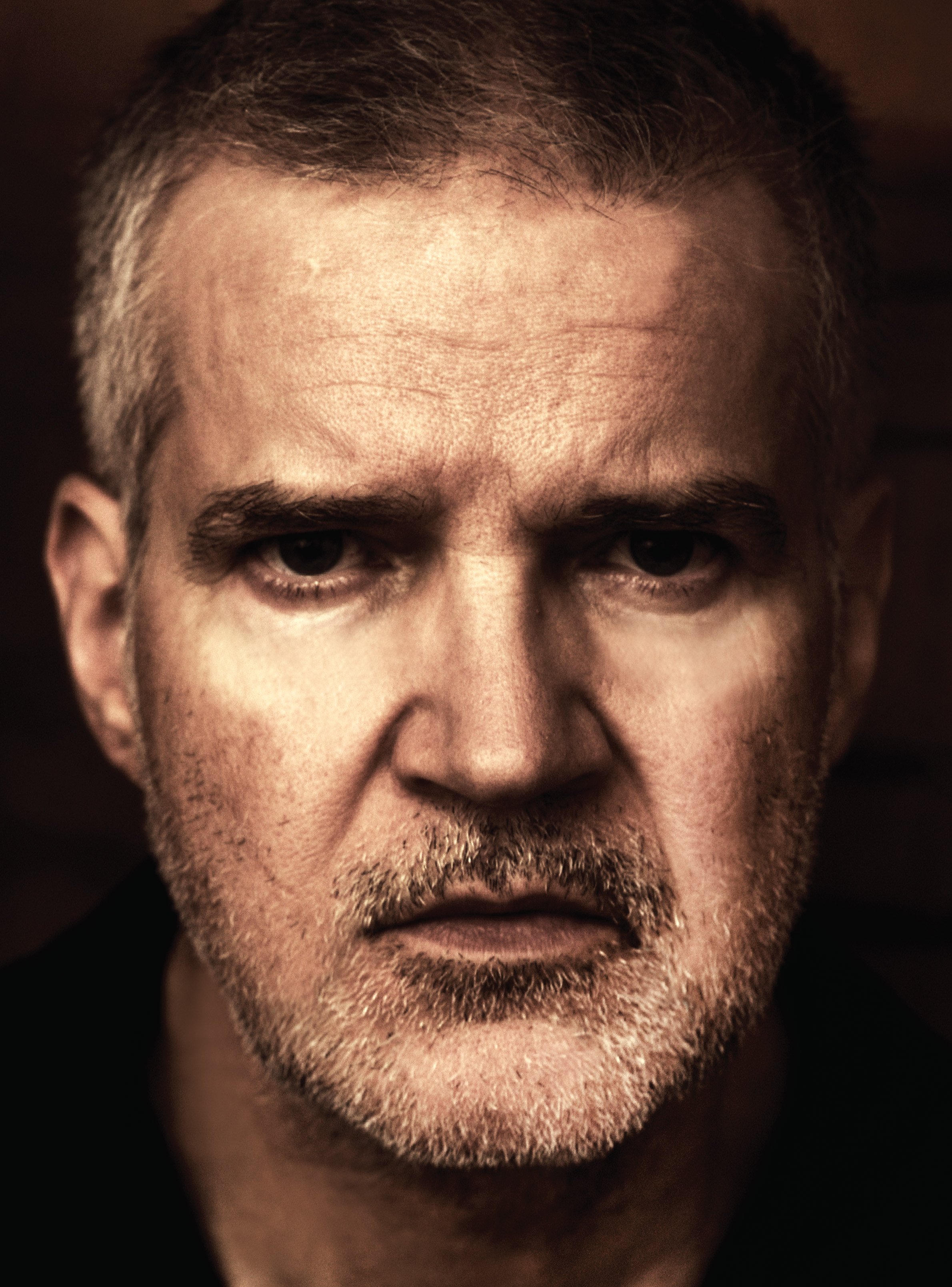

It’s quarter to ten on a Tuesday at SPoT Coffee on Main Street in Snyder, New York, at the height of July, and the patio is bright, hot, and as empty as the sky. Tall and slim with very close-cropped gray hair, Cole blends in with the other SPoT patrons–in a black polo and jeans, he could be just another suburban dad catching a few minutes’ peace after slipping his kids some change to buy smoothies inside. In many respects he fits this profile: He lives in Easthampton, Massachusetts with his wife (of 20 years) and two children. He enjoys gardening, biking, and audiobooks. He tweets–like other men his age, mostly about politics, soccer, and golf.

But Lloyd Cole is also a celebrated–iconic–musician and songwriter, with the kind of dedicated following that passes by most celebrities and sticks only to those cultural meteors who, whether in a direct hit or glancing blow, make us feel when we first encounter them that the course of our life has been somehow altered. Since the early 80s he’s made the kind of music you only share with the right friends, the ones you know can get it. Other musicians and writers in particular admire him: Karl Ove Knausgaard, to pick just one example, devotes a passage in My Struggle to the impact of his music.

Cole grew up in small-town Derbyshire, England, and was on course to become a barrister when, after a year at University College London, he transferred to the University of Glasgow to study English literature– “what I wasn’t good at,” he recalls. It was there that he met Blair Cowan, Lawrence Donegan, Neil Clark, and Stephen Irvine, who would form The Commotions in 1982 and release Rattlesnakes two years later. Debuting at Number 13 on the UK charts, the record brought the group overnight fame that propelled them through two more top-ten albums, Easy Pieces in 1985 and Mainstream in 1987. They checked most of the hot new band boxes–playing Top of the Pops, signing with Polydor, once finding the reclusive Morrissey waiting backstage for them after a show–before dissolving amicably in 1989.

Rattlesnakes handcuffed Cole to lazy music-press descriptors that once, at least, must have incensed him– “post-punk’s most articulate songwriter,” he quotes for me, disdainfully–but unlike most of his contemporaries, he’s never succumbed to what other people, fans and critics, seem to expect of him. His albums have cruised through lush rock and spare folk, flirted with country influences and instruments, and pivoted to electronica. His experiments include 1D, an album of almost entirely unfinished electronic compositions originally meant for a collaboration with Hans Joachim Roedelius. Cole doesn’t mind pretention–there’s something inherently pretentious about making “art,” he observes on Twitter–but he’s studiously free of affect and false certainty. His pursuit of honesty and precision strikes one as a practice, almost like vipassana meditation for serious adherents–it’s evident in everything, even the haircut.

But it’s most evident in conversation. There’s something boyishly serious about his face, perhaps in the cast of the cheeks gently tugging his mouth into a pensive pout, under a brow as solid as an architrave. He laughs only once in the hour we sit together, but he isn’t brooding or cynical or any of the things incompetent critics have called him. He’s frank, open, and interested in everything worthy of attention. His response to the world, when he has one, is essentially a creative act, a composition: He’ll play out a few words and repeat them until the next words fall into place, the way he might reach for a finished melody by trying out the first notes, over and over again, listening for a hint in the silence that follows. Making conversation, making art–these are necessarily acts predicated on hope.

Lloyd: ...You know with my music, believe it or not, people have referred to me as a cynicist for many years. How do you get that from my work? I mean I might write about characters who have become cynical but that doesn’t make the writer...I mean how could you really be a cynical writer? Because if you’re a cynic, you’ve given up hope, and if you’re writing you’re constantly putting stuff out there, which is essentially hopeful. So how on earth can you be a cynic? I gave up worrying about it years ago.

Aidan: So I know your mode isn’t autobiography, but I have to ask: I think it’s in the song Speedboat, you write about a “great unfinished novel.” Have you ever worked on a novel?

No, I’ve never even started a novel. I do have a couple of notes for possible stories. But I’m really not that interested in going in that direction. I still feel like there’s a lot of work to be done with music. I’ve had a few commissions to write nonfiction, and I accepted them to try and find out if I have any kind of a prose voice, and it seems like I do, but again, I can’t really afford to pursue it because I’m a slow writer, and the amount of time it takes doesn’t match the remunerations, so I can’t really afford it.

On Guesswork, there’s such a clear contrast from your earlier work with the Commotions in terms of the lyricism–it’s so shrunk down. Was that a natural process or a conscious choice?

Well I felt like I was becoming more and more concise over the years, but then the last record I made before this [Standards] was very flowery and quite busy. So it just comes and goes I guess. It definitely wasn’t a decision for this process to say, OK, this record is going to be very spare lyrically. It just was. It’s not super spare. But it’s the longest album I’ve made, in terms of [play] time, and it’s got the least number of songs and the least number of words.

Yeah. Well it’s certainly less overtly allusive, there are fewer adjectives...

The last one was almost a kind of return to a feeling of my very early work, which was playful with language. And I still enjoy the idea of being playful with language. I found myself singing a song recently, from the late 90s, that I thought was one of my best lyrics for many years. And now I think, singing it, it’s maybe a little too...just clever. Yeah. Late Night Early Town. Which I do think has got some good stuff. But there’s a line in it...“Strung out on semantics, Holiday Inn vigilantes”…which I always thought for a long time was one of my better lines, and it’s clever. It’s a good rhyme for sure but...“Holiday Inn vigilantes” is quite nice but “strung out on semantics” might be just a bit too much. But I was thirty-five, thirty-six, thirty-seven when I was writing that song and...I’ll excuse myself. It’s just maybe a little too arch.

I was reading an article or an interview with you in The Guardian about your last album and you said you were thinking about whether it was appropriate for you to be writing–as a musician in middle age–and then you sort of felt like, fuck it, and made the album.

Aging is interesting. There’s something about middle age that nobody seems to like. Young people don’t like middle-aged people, middle-aged people don’t like middle-aged people. Old people don’t like middle-aged people. Nobody really wants middle-aged people to exist. It’d be great if we could just wipe out middle age. And certainly in terms of my reception as an artist...I’m doing way better now [that] I’m basically old. I’m doing better close to 60 than I was doing close to 40. I’m playing bigger venues. I don’t know. I think people just don’t want that in-between area. They want you to be either young and fresh or an elder statesman.

So I was born in 1993. You had already been writing music for a while. Have you found that you have picked up a lot of fans who weren’t born or listening to music at least, during your “first act”?

Definitely some. When I look out at the audience, it’s not all people my age or thereabouts. There’s the offspring factor, definitely kids hearing their parents’ music, and there’s the younger sibling factor. My wife is more active than I am on social media with forums and what-have-you to do with me. I basically just put stuff out there and try to just...hit the Like button every now and again, but I try not to interact too much. But my wife tells me that it is really fun when some millennial comes along and they just heard me for the first time and now they’re excited about it. That’s a fun thing to hear that it can happen.

I guess I’m kind of curious about the 30s, 40s period. You sort of come up as an artist with an audience close to you in age, typically, and it’s possible that watching an artist evolve into their 30s and 40s it reminds the audience of themselves too much.

Also, during that period, typically, people are having families and children and mortgages, and they don’t have as much time to be indulging themselves in the music that they like. And there’s certainly a feeling I got by the time I had two kids. I definitely remember there was a Morrissey album that came out–before we knew that he was an alt-right guy–a long time ago. I think it was the album before Your Arsenal, whatever that album was. And I remember listening to it and going, This is fine but...I’ve got enough Morrissey music. So I can totally understand if people would feel that way about my music as well. I’d probably like to flatter myself to think that my body of work is at least a little bit more diverse than his. I feel like he just makes the same record over and over and over again, and I try not to do that, but that doesn’t mean I succeed. But I do feel that narrating from exactly the same point of view for 30 years consecutively doesn’t make regular sense to me. It seems that is what Morrissey has done. So if it’s happened to me listening to other people then I can quite see how it could happen to other people listening to me. You don’t have time, or you just you feel like you...like your heart is full, and there’s not room to add more stuff. There is definitely a middle-life feeling.

And there seems a freedom in old age, and it probably has to do with the fact that the kids are no longer in house, you don’t [need] to look after them, and you have this kind of subconscious feeling that...My wife says since she stopped dyeing her hair, she can get away with anything. Like if she asked a young person to do something in the street they’ll do it. They just do stuff for you when you’re old. They would just ignore you when you weren’t.

...You know, certainty–I mean anybody that reaches 60 years old and is absolutely sure about something is either a zealot or an asshole. Or an idiot. Certainty is dangerous. That’s why religious people are so dangerous. Because they’re sure about something. So I think one of the things in old age is you realize that if you were ever searching for some kind of absolute...black and white becomes gray. And gray becomes actually more appealing than black or white. So that’s where I’m headed.

Are you familiar with the lyrics website Genius, where people can annotate lyrics? You can go on that website and for your songs, many of them are up there, people have highlighted a section, and they’ll say, like, This is what this means. Do you find that difficult, as an artist, knowing that you want to steer away from certainty toward ambiguity, toward the gray, and being expected constantly to have a definite meaning?

Well I’ve tried...My public position is pretty clear on songwriting. My belief is that your understanding of my song is necessarily correct. And your understanding doesn’t have to be the same as his understanding. They’re all necessarily correct. And there’s two ways to legitimize that way of thinking. One is obviously the philosophical death-of-the-author concept, which I think makes sense. But the other one is...let’s just say that I was didactic. Let’s say for example that I really did have a specific message I wanted my song to impart upon the world. Well. If everybody didn’t get it exactly the same way, then I got it wrong, and I’m a bad writer. And I think–this is not logically correct, but statistically the chances of everybody getting it exactly right are very close to zero. So the idea of being didactic is a fucking waste of time as well. So I think both positions, both arguments, both work in favor of leaving room in almost any art for some elements of the reflective–the reflective being that the listener or the viewer or the reader is an important part of the deal.

I think generally speaking, certainly Western society vastly overvalues the creative people, the writers, and vastly undervalues the readers. Without the readers there’s no job for the writers anyway. The readers need to be there to give value to the work. The work’s got no value without the readers. The work is effectively a tree falling down in a forest miles from anybody, if nobody reads it. So the idea that any work of art can actually have intrinsic value is moot in my opinion.

It’s hard to imagine how somebody like Kafka wrote for years without ever having had an audience–he didn’t have an audience until he was dead. That’s very hard to imagine.

I think when you were talking to The Guardian about Standards you said it wouldn’t be your last album with lyrics, and that you were writing stuff down in your book toward the next one. Has that always been your songwriting process? You have a book and things compile and then–

The older I get the more notebooks I have and the less I write in them. It used to be I would have one and I’d write everything in it, and now I feel like once I start working in earnest on songs I really need to split them up into different books so I don’t get confused about what is supposed to be going here and what must be going there. So by the end of all of the Guesswork project I had at least five books which were probably split for two songs each, starting at the front of one and the back of the other, just kind of working my way through the songs. But I do always have a book that’s with me when I’m traveling. And I did have ideas as I was finishing Standards, and one of the ideas was the song that was called Guesswork, which became The Over Under on the record. But it took me years and years and years–it took me about five years to somehow muster up the energy to take on the project.

So the oldest material on Guesswork is about five years old?

No. No...No, there’s some music on Guesswork that’s from 1987. I found a cassette that Blair [Cowan] gave me in 1987. And it was a song idea that I wanted to do something with and I’d put it aside and then forgotten about it. And I sent him a copy of it last year and I said, “Can we revisit this?” [laughs] And that became When I Came Down From The Mountain. And the other song that he co-wrote, which is called Remains, that’s an idea of his from before Standards. It’s an idea of his that I’ve had, and I’ve had it filed away as something I wanted to try and turn into a song, but it’s quite an abstract piece of music without the singing. And it was quite a challenge; probably the biggest challenge on the Guesswork record was to turn that idea into a song. It doesn’t have a sort of ABC verse-chorus-verse-chorus structure like most songs have. It’s a little closer to a show tune. I was lucky that I spent a lot of time studying Stephen Sondheim a couple of years ago. And I don’t love everything he’s done but I do like a lot of his work. And just seeing that the way songs can work out away from rock and roll dance music templates–it’s exciting. Challenges are fun. I like challenges in my life.

You have to admit that it’s really tempting to hear lyrics about “coming down from the mountain” in autobiographical terms when you’re working in an attic alone for eight or 10 hours a day on something sort of monastic.

Yeah, absolutely. I think there’s no way of escaping the fact that a large number of people assume that all art is autobiographical. When somebody sings “I”…And I no longer worry about it. I think if you pay any attention to the work that I’ve done over the years there are so many logical impossibilities of it all being the same guy–how could it possibly be the same guy if he sings this one time and he sings that another time–how could that be the same guy?

It’s almost like an alibi–like, no, I was over here.

Yeah, yeah, exactly. Exactly. It is an alibi. Yeah. My wife, she was giving me shit the other day about some of the songs on Standards. She was down with Jack, down with her stepmother and they started playing my record, and she said, “You start singing about taking somebody to your hotel room?” It’s like, “It’s not me!”

So I wanted to ask about the sound of the record [Guesswork]. There’s this sort of rock element, there’s the singer-songwriter element, there were some of the weird structures like we were talking about, from studying Stephen Sondheim, and then obviously there’s a Roxy Music influence, songs like Violins and others. Did you have all of that in mind when you set out?

I think one of the reasons it’s very difficult to talk about music, one of the reasons that rock criticism is quite difficult, is because finding the language to describe sonic stuff is quite difficult. So I think a lot of the time we end up necessarily talking by using comparisons and examples of things that already exist, and things that might be possible. So, when I started thinking about the project, my sort of pet name for the project was that it was going to be my take on Iggy [Pop]’s The Idiot meets [Scott Walker’s] Scott Three. That was kind of what I was thinking–I think I could do something that has got a synthetic base to the sound, but still has–that it’s not a cold record.

A lot of the instrumental music that I do comes from approaching the instrument in almost an academic frame of mind. Quite often I’m not trying to make music; quite often I’m trying to learn how to work with a particular oscillator or something. And then because I’m a musician, not a technician, if I’m doing that and then all of a sudden I hear something, it quite often leads to music, in the same way that if I sit down at the piano–I’m not really a very good pianist–but if two chords all of a sudden sound good together to my ear, that can quite often be the seed of a song.

Does language work that way, too, where you’ll encounter some juxtaposition of words and that leads to a song?

Absolutely. That’s probably the most common, kind of seed for a song, would literally be just one or two words that I like the sound of them together.

You mentioned “Holiday Inn vigilantes”...

Yeah, absolutely. Those are the things that are usually in the notebooks. It’s not usually long passages, just usually a few sentences or even just a couple of words. And I have a pool of potential song titles that I think, these could be something.

Do you already have a framework for the next record?

I do. It’s going to be...If this was Scott Three and The Idiot, the next one is going to be [David Bowie’s] Low and [Scott Walker’s] Tilt. It’s going to go more extreme in the two directions. There’s gonna be shorter songs. And there’s probably gonna be some instrumentals on the next record.

Do you think it’s going to take another six years, and you’re gonna do it alone?

No. I’m not sure how I’m going to do it. In an ideal scenario what I’d really like to do is just get the three main guys from this record, and Chris Hughes in a studio just for a month and just do it really quickly. That would be fun. But for me to do that, I would have to write the songs first, and have them ready. I’m not sure if that would make sense for a record which is gonna be somewhat experimental, because maybe I need the flexibility to be able to take the songs in different directions. Maybe the lyrics need to be malleable, maybe they don’t need to be written in stone.

It’s really hard–probably the hardest thing about working alone on music is you really do need about four different hats. You need a producer hat, you need a lyricist hat, you need an arranger hat, and you need a technician hat. And I found it, over the years, almost impossible to go from technician to lyricist in the same day. For example when I was making Antidepressant, I was programming the drums in the computer working with a virtual drum, which I ended up enjoying the sound of, and I’d work for maybe six hours on something like that, and then I’d think, OK, now I’ll take a break, get some lunch, now I’ll try and write lyrics, and I just couldn’t do it. I couldn’t write lyrics. In fact I couldn’t write the lyrics to Antidepressant until I was away from the studio completely. I actually finished most of the lyrics for that record when I was on tour in Germany. Like, away from being a technician completely. So, one of the challenges of making a record is to be able to go from different ways of thinking about the end product and the music, and to realize that there are logistical limits which are frustrating, but they have to be recognized, otherwise you just waste a massive amount of time just trying to do something which is just not realistically possible.

Do you find that you’re becoming more efficient, simply because you’ve worked through these problems and understand your mind and processes better?

A little bit. I probably don’t have as much fire-like energy that I would have had when I was younger, but I do think I waste less time.

You know, I would have probably been quite happy to retire from music about 20 years ago. But I wasn’t able to. Economic freedom isn’t discussed as much as it should be, when it is just as important as artistic freedom. I don’t have economic freedom. I don’t have the means to choose what I’m doing at any given time, I still have to work, and making music that I want to make within the framework of the lack of economic freedom is a challenge.

You talked about playing bigger venues now than you were 10 years ago. Has that energized the artistic side of the process, just finding that people are responding in greater numbers?

…I don’t think so. No. Adding to the body of work seems to be an exponential challenge. Right now I’m feeling excited...One of the reasons I think I’m going to make the next record quite quickly is because a lot of the work that was necessary to make Guesswork possible was very tedious logistic stuff. It was like getting my computer working to do music again when I hadn’t done any recording in my studio before, getting the software up to date, knowing how it works. It’s a massive amount of work, but I did that for this project so I sort of have a system in place which would make about 40 percent of the work that I did on the last record not necessary for the next record. But there’s no guarantee that I’ll be able to finish these song ideas quickly. There’s no way of knowing, really. I’m hoping I can but I might hit a brick wall.

I was talking before about readers being arguably more important than writers ... The term “writer’s block” in my opinion is bullshit. Writer’s block is just normal life. Not being creative is normal. Being creative is abnormal. Being creative, having a creative spark or being inclined to want to make something to show other people...having the confidence that you’ve got something that you think is good enough to show other people–that’s not normal. And that’s not something that happens, it’s not a feeling that is the normal feeling in one’s life every hour of every day.

If you look at people that we consider the great writers, great performers, most of them burn out and most of them reach a certain point whereafter they don’t create any great work. But they continue to add–a lot of them continue to add to the body of work. And that is my kind of nightmare. I hope that when I’ve got nothing more to add, I hope I don’t add any more. I don’t want to just keep putting stuff out for the sake of putting stuff out. I’m not interested in feeling good about myself. I’m interested in making the stuff that excites me. And if I don’t have that...I got plenty of other stuff to do. I like gardening. You know? And my garden needs me. I never have enough time to be in the garden because I’m doing other things.

I think being a reader is more normal than being a writer. And for me...I don’t think I write very well if I don’t read. I think my writing gets dull if I’m not consuming other stuff, if I’m not finding excitement in somebody else’s use of language or somebody else’s sonic creation or whatever. I think when I’m working on a record I still like to be working in a kind of a vacuum, but in between those vacuum stages I need nourishment.

Maybe one type of labor refreshes or gives you more energy for the other, but it’s still labor. It makes me think that–you know you say that reading is maybe a more natural state than writing, but too often I think we think of it as passive. And it shouldn’t be.

Exactly, yeah, yeah. Let’s see if I can remember his name... it’s a Marxist art critic from early 20th century...I can’t remember his name. But he has a definition of kitsch. Kitsch is the stuff that requires no effort from the reader. That’s a great definition of kitsch from my point of view. And art requires a reflective element. Art demands–art makes demands on the listener or the reader.

Art demands an answer, essentially.

Art demands an interpretation. Art demands that you use your humanity, your very particular individual humanity, you use your individual humanity to find your...“understanding” is not necessarily the right word, but to find your way to consume the art.

Which is perhaps a practice of guesswork.

Yes [laughs], absolutely. Absolutely. Depending on how didactic the art is. Oscar Wilde’s quote is the best one, I think. He says “If I only need to read a book once why should I read it at all?” So I think, you know, I’m certainly not alone in thinking this way, but if you create with a view to not limiting the listener I think you possibly have a better chance of succeeding at creating something that people can find beautiful.

in print discover issue twenty two