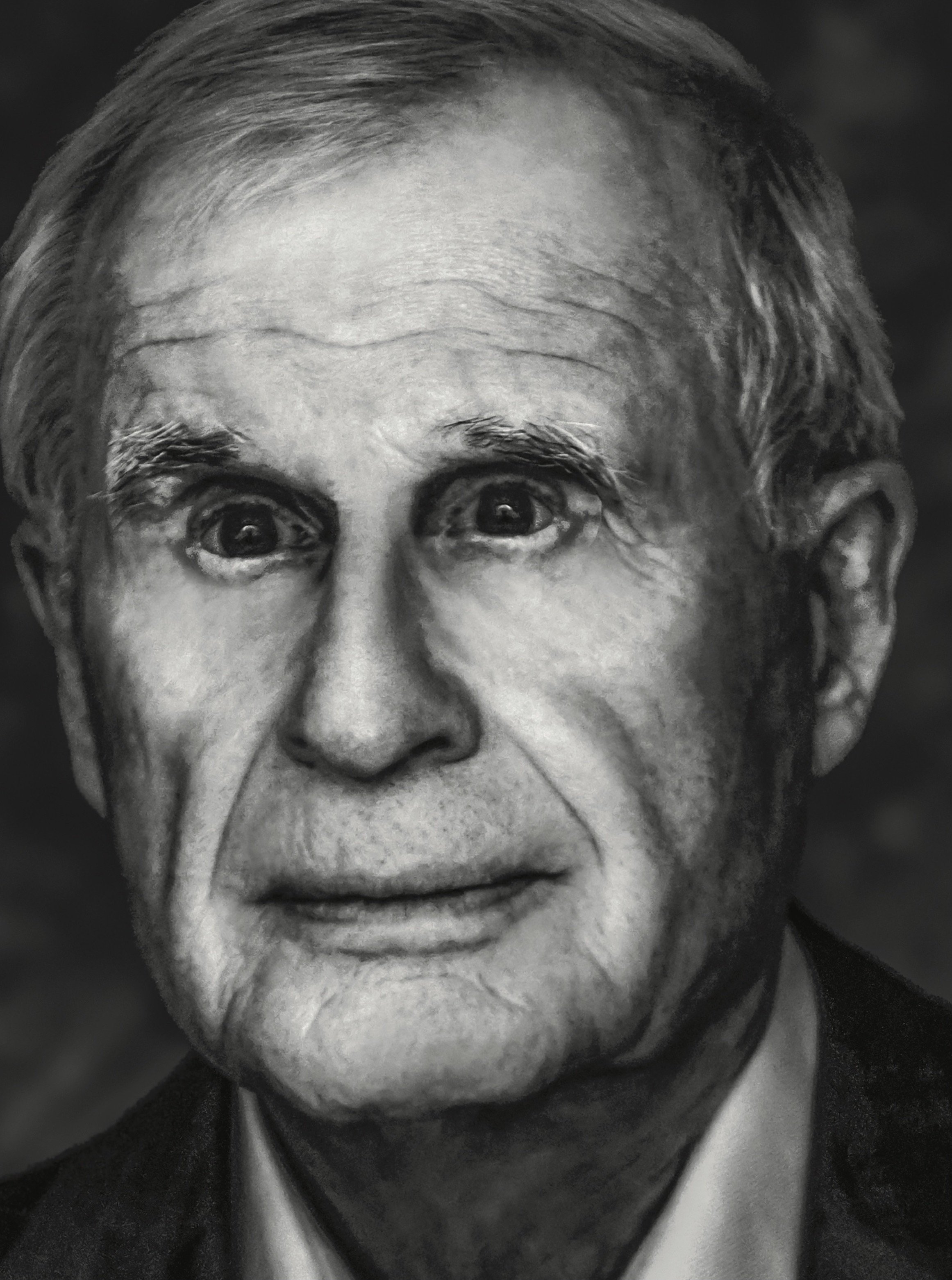

patrick lee: an american story

Of self discovery…

There is a time in every man’s education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance, that imitation is suicide; that he must take himself for better, for worse, as his portion; that though the wide universe is full of good, no kernel of nourishing corn can come to him but through his toil bestowed on that plot of ground which is given to him to till. The power which resides in him is new in nature, and none but he knows what that is which he can do, nor does he know until he has tried. God will not have his work made manifest by cowards… Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string. Accept the place the divine providence has found for you, the society of your contemporaries, the connection of events. –Ralph Waldo Emerson, Society and Solitude

Of life purpose…

What we are, that only can we see. All Adam had, all that Caesar could, you have and can do. Adam called his house, heaven and earth; Caesar called his house, Rome; you perhaps call yours, a cobbler’s trade; a hundred acres of ploughed land; or a scholar’s garret. Yet line for line and point for point your dominion is as great as theirs, though without fine names. Build therefore your own world. As fast as you conform your life to the pure idea in your mind, that will unfold its great proportions. –Emerson, Nature

Of personal power…

Life only avails, not the having lived. Power ceases in the instant of repose; it resides in the moment of transition from a past to a new state, in the shooting of a gulf, in the darting to an aim. This one fact turns all riches to poverty, all reputation to shame, confounds the saint with the rogue, shoves Jesus and Judas equally aside. Why, then, do we prate of self-reliance? Inasmuch as the soul is present, there will be power not confident but agent. To talk of reliance is a poor external way of speaking. Speak rather of that which relies, because it works and is. –Emerson, Self-Reliance

I

An Elusive Subject

m. dellas

I begin with Emerson’s insight into the American character to write about Patrick Lee to provide a lens through which to see and appreciate Lee’s life and work. How to get a handle on a man who has singular achievements to his name in both the profit and non-profit sectors but who isn’t much interested in discussing the past or dwelling on the road to his success? After some time searching for a key to unlock the “inner self” of one of Western New York’s major business leaders and philanthropists, it occurred to me that Patrick Lee is, in many ways, a quintessential example of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Individual. In 2013, Lee was inducted into the Horatio Alger Association and given its highest award which recognizes “persons of outstanding character, whose lives and actions demonstrate the power of the human spirit…unwavering commitment to their goals, their prodigious accomplishments and their enduring impact on their respective fields…[recipients] exemplify perseverance, personal initiative, integrity, leadership, commitment to excellence along with belief in the free-enterprise system and the importance of philanthropy.” All of which is an accurate description of Lee and his remarkable achievements. But the celebrated ethos of the Horatio Alger Association (named for the Gilded Age “rags to riches” novelist) whose members include some of the wealthiest entrepreneurs and industrialists in the nation as well as leaders in professional sports, entertainment and the arts, and other fields, falls short of identifying the psychological or, better, the spiritual chemistry unique to high-achieving Americans. Emerson, one of the first Americans to contribute to world literature, offers compelling reasons for American success. He probes the existential resolve that propels Americans to achieve. Writing in the 1830s, his pulse on the heartbeat of the young nation enabled him to identify commonly shared attributes of the individuals who built American commerce and culture. What makes his insights so compelling is their continuing relevance from the settling of the continent to the present day.

Emerson’s journals and essays, which were his primary contribution to American letters, depict what Harold Bloom, his greatest critic, if not disciple, calls “the Newness [and] influx of power.” In the 1830s, by which time the nation was well enough established to have acquired a discernable social and cultural “persona,” Emerson identified what Bloom names “the American stigma of genius.” “Genius” because it created out of whole cloth a republic unlike any heretofore in history; and “stigma” because, human and flawed, the blessing of its genius was not without the marks of its curse. The American character Emerson identifies was literally and figuratively the crossing to a perpetual newness, a relentless putting into action of a vision to possess, settle, and expand the physical, economic, political, and cultural footprint of the country. That Americans pursued these ends regardless of risk, not infrequently ignoring moral or ethical boundaries, accounts for our opinions and attitudes about greatness and success.

Thus did religious dissidents cross the Atlantic to establish a new society free of the oppressive limitations and corruption of the old world. This “crossing into newness” continued as Americans ventured west and settled a vast wilderness by 1890. The American story unfolded as the country met and endured civil war, world wars, cold wars, and threats to national self-interest and security while building the most prosperous economy of all time. This defining feature of action–of crossing to new lands and opportunities which Emerson terms “shooting through a gulf and darting to an aim”–is neither an innately humane nor moral quality. Rather, both good and bad consequences resulted, not just the founding of representative government and an open economy but, for example, the degradation and segregation of indigenous peoples and the horrid history of slave-holding. Which does much to explain the presence of two diametrically opposed streams of the nation’s legacy as well as the present deeply polarized society we live in. Emerson’s guiding principle, woven into and the animating force behind the nation’s push to settle and prosper, was what his young admirer Friedrich Nietzsche called the “will to power”–a perpetual impulse and capacity for taking personal action–that transcends but is often used to further political ideology, religious doctrine, and moral and ethical tenets as well as economic and artistic aims.

Patrick Lee’s ultimate concern and focus in business and philanthropy are consistently two things that have fascinated him since childhood: solving problems by finding the best solutions. That “calling,” if you will, defines how he spends his time and with whom. Indeed, he gave permission to be interviewed for this article only after it was pointed out that it could benefit the wider mission of his foundation. Giving his time to anything that doesn’t serve his aims and the larger good of his foundation to benefit others is of little or no interest to him. Consequently, his foundation is well known among those who serve foundations with similar missions and he is regarded with deep respect and admiration not just by those who benefit from Lee grants but by his peers in the philanthropic community.

After researching Lee’s business and philanthropic accomplishments and hearing from some of those who know and have worked with him, even after interviewing him the first time, I came away with the feeling that I had yet to discover the real man. The image that emerged from these preliminary impressions was more of his curricula vitae, lacking the human qualities that led to and were in turn shaped by what is indisputably an impressive life journey. Patrick Lee achieved rarified success in professional life, made original contributions in highly competitive, tech-driven marketplaces and, after creating significant wealth, established a major Western New York philanthropic foundation. What I was searching for was the person who pursued and reached such rarified success.

My initial assumption was that Lee would enjoy reflecting and commenting on what led him to such great accomplishments. Yet, he responded to my questions with brief, impersonal answers. His responses were not impolite but revealed his disinterest in spending (or wasting) time sifting through the past–“life only avails, not the having lived” as Emerson said. His entire modus operandi of which I was becoming aware and that revealed a complex personality may be defined as the pursuit of purposeful action to bring about far-reaching aims–as in Emerson’s “shooting a gulf,” and “will to power.” Therefore, I came to the second interview with more pointed questions and a determination to find the man behind what appeared to be an indifference to recounting personal history. The meeting took place in the boardroom of Lee’s foundation with Jane Mogavero, the executive director of the foundation, present and exceeded two hours, surpassing the allotted sixty minutes. Lee shared personal stories, challenges of growing his business, even his views on the current volatile political climate. I also sought out and met with two of his long-time friends and colleagues who worked closely with Lee and wore multiple hats as members of his corporate board, foundation board, and boards Lee chaired in the community. Those meetings led to sessions with senior officers of a major Western New York institution Lee’s leadership helped transform. Finally, I gathered insights from a handful of others who knew Lee by reputation. The picture that began to emerge was of a man who defined himself by his actions in the present, who regarded his past as helpful insofar as life has lessons to teach, yet rather than a resume to fill or reputation to build, Lee was, and is still in his early 80s, a man who seeks and lives in the moment, pursuing meticulously planned, vigorously executed strategies to achieve calculated and lofty goals. From high school to the present Patrick Lee has been like a ship at sea, cutting through whatever weather or currents his course encounters.

II

Success By Any Measure

After piecing together the chronology and benchmarks of his path to success, it was clear that Lee, in Emerson’s words, seized “the power residing in the moment of transition…to a new state.” If his life were charted on a navigational map it would show a bold line from smaller to larger aims with little deviation. Lee went full steam forward: from earning his way as a teenager doing summer farm work for room and board at $5 a day as an only child whose father was killed in World War II and whose mother had limited means; to coming to Buffalo out of college to work as a freshly-minted engineer for an aeronautical firm then, five years later, founding his own company with $2,500 and twelve employees in a machine shop; to building that business into one of the most successful startups in Western New York; to anticipating the shift and impact of global automation by designing patented products for newly emerging technologies; to hiring the right managers, and assembling powerful boards; to marketing and selling an increasing inventory of motion control devices to a wide range of customers beyond the aeronautical industry; to creating a highly efficient, aggregated business model before Peter Drucker was talking about business models; to acquiring international partners and facilities on the eve of massive international growth just as the world economy began achieving independence from the post-war GNP of the United States; to making a nearly seamless transition selling his firm to a Fortune 100 company then founding, equipping, and launching one of Western New York’s major foundations. Even in his service to the community and nation–as chair of the first board of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center not only to build the board, its policies, and working relationship with the State of New York but to regain its prominence in excellence as a cancer treatment hospital and pioneering research center, or chairing the board of the Western New York branch of the Federal Reserve Bank among other leadership roles–Lee fought with the same resolve and commitment that he devoted to his own business and philanthropic enterprises to make change where it was needed to ensure success.

Patrick Lee isn’t just an engineer or entrepreneur, his ability to master marketing and sales strategies is equal to his skill at patenting motion control devices. His skill at growing and managing an international firm comprised of global companies from the United Kingdom, Europe, and Asia and finding and hiring the right people to oversee such distant enterprises is a textbook example of how to start, grow, and position an international business for long term profitability. His given talents were honed and his learned expertise hewn by a nearly flawless “gut instinct” in business, eschewing from his boards and staff leadership “yes” people, and practicing himself a fearless trial and error approach to building his company and then his foundation. The proof of his ingenuity and ability to master almost any skill needed to expand his business is in the vision he had and goals he realized, especially those that enabled rapid growth to scale for global capacity.

In addition to his uncanny “Midas touch” as a manager is a nuanced, intuitive attention to people, nurturing and strengthening relationships within the organization that generated an esprit de corps to which employees and boards of directors pay loyal and enthusiastic tribute. That element of creating a rewarding social environment in a high-achieving organization comprised an iron bond of admiration, respect, and devotion to Lee himself. Several said the devotion goes two ways, that Lee is genuinely interested in their personal lives and would stand by and support them if needed.

Whether mapping the pace and stages of a multi-day board retreat or meeting for an intimate dinner with Lee and his wife, he plans in granular detail months in advance. For example, when dates are made, he might suggest conversation topics with future dinner guests or arrange “down-time” recreation tailored for each board and staff member and their spouses. One colleague said that Lee takes entertaining to another level. The old adage “prior planning prevents poor performance” could be his mantra. Faith in Lee as a leader and trust and admiration for him as a human being gave his business organization and now his foundation surpassing teamwork, communication, and decision-making rooted in frank feedback, and, almost as a litmus test for cohesiveness, the open admission (by everyone including Lee himself) of mistakes to learn from and avoid making again.

Lee keeps exceptionally high standards for himself and expects the same but not more from others. He is widely read, does his homework–research might be a better word–and looks for the same preparation from all, “yesterday if possible” as someone put it. He is capable of passionate disagreement and encourages debate in business and board meetings when important decisions are at stake. His communication with colleagues on such occasions can be perceived as demanding and pushy. Yet, when brought to his attention, he accepts feedback and asks to be told if and when his zeal crosses the line. One veteran board member said business disagreements never become personal, and that Lee separates board room disputes from day to day working relationships.

III

The Emersonian Individual

Emerson’s great essays could almost be read as spiritual portraits or credos of the first colonists who literally built the first villages and found a way to survive and provide, to the revolutionary generation who met and defeated overwhelming odds to break away as a nation free of monarchical rule, to the pioneers who pushed west with an insatiable appetite for opportunity. Anything less than total commitment, among the first generations of Americans, to a personal stake in the larger collective purpose of building a nation and establishing a particular form of government and economy would have kept America a colonial outpost. But something that could be called American spirit or character coalesced around a cluster of not just values but successes that gave the nation a reputation for freedom and opportunity for any who found their way to these shores–a reputation albeit never completely lived up to and sometimes even abandoned. Yet, as partial and fragmentary as it may have been, it always stood in bold contrast to the rest of the world. Freedom and opportunity were manifest consistently enough to attract those from every corner of the earth who aspired to live out their own life’s purpose in a land famous for the promise of fulfilling such dreams.

So it was that Emerson identified an American “profile”–traits and characteristics that were in evidence from the beginning and continued to appear, less so perhaps among the common citizenry as the nation progressed from an agrarian to a post-industrial society, but clearly traits that are still the defining, driving influence of leaders in every sector of American life. From the founding fathers who were themselves entrepreneurs, philosophers, inventors, to the MacArthur Prize winners, from the preachers of America’s Great Awakenings to the New England Abolitionists to the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement and Martin Luther King, Jr. they had in common an uncommon dedication to their calling and life purpose. Of equal significance is the relentless passion of the nation’s industrial barons and innovators who built the nation into a superpower. Andrew Carnegie, Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Thomas Watson, Steven Jobs, Bill Gates, Elon Musk to name a few. And the women who fought for a level playing field from Susan Anthony to Gloria Steinem to Oprah to Tarana Burke. Like them or not, they each embody the “stigma of American genius”–Emerson’s will to power–that tells an accurate and complicated story of the success of not just individuals but the nation itself.

Emerson was not a systematic thinker. His work is a prolific collection of aphorisms on a wide range of subjects from personal fulfillment and society to human existence and the natural world. Emerson scholars claim it would be impossible to summarize or codify his thought which is best grasped by delving into it. Here is Emerson from The Conduct of Life on the individual and the will. It’s fair to say most people embody, in part, the wisdom described here. But there are always those in every strata of American society who reflect these truths more completely. Such is the case with Patrick Lee:

Regarding his early circumstances and upbringing: Great men [sic], great nations, have not been boasters and buffoons, but perceivers of the terror of life, and have manned themselves to face it.

Regarding his presence as a leader: I cited the instinctive and heroic races as proud believers in Destiny. They conspire with it; a loving resignation is with the event... Let man empty his breast of his windy conceits, and show his lordship by manners and deeds on the scale of nature. Let him hold his purpose as with the tug of gravitation. No power, no persuasion, no bribe shall make him give up his point. A man ought to compare advantageously with a river, an oak, or a mountain.

Regarding his pursuit of purpose: He who sees through the design, presides over it, and must will that which must be… Our thought, though it were only an hour old, affirms an oldest necessity not to be separated from will… It is not mine or thine, but the will of all mind. It is poured into the souls of all men…

Regarding moral order and his aim to do the “right thing” including using his wealth to serve others: If thought makes free, so does the moral sentiment. The mixtures of spiritual chemistry refuse to be analyzed. Yet we can see that with the perception of truth is joined the desire that it shall prevail. That affection is essential to will. When a strong will appears it usually results from a certain unity of organization, as if the whole energy of body and mind flowed in one direction. There is no manufacturing a strong will. There must be a pound to balance a pound. Where power is shown in will, it must rest on the universal force.

Regarding his implacable resolve: The one serious and formidable thing in nature is a will. Society is servile from want of will, and there the world wants saviors and religions. One way is right to go: the hero sees it, and moves on that aim, and has the world under him for root and support.

IV

The Cradle and Crucible

Much about a person is rooted in the foundational years of early childhood and youth. While Lee was not averse to discussing his formative development, he was circumspect in answering my questions, yet still provided information that offered revealing insight into his adult life and work. Lee’s parents met in Berlin at the 1936 Olympics when Lee’s father was serving in the US Navy and his mother was competing for France in the swimming competition. Born in Portsmouth, Virginia in 1938, his childhood was scarred by the tragedy of his father’s death when his ship was sunk in the Battle of Guadalcanal in 1942. Lee, an only child, and his mother moved to Paris, France in February 1939, where her family lived when Lee was then four months old and did not return to the United States until the age of seven. The years in France had a profound, far-reaching impact on both his business career and commitment to philanthropy.

Lee’s first language was, naturally, French. If not a Francophile, then Lee is a person at home in French culture and comfortable with cross-cultural settings and experiences. He continues to talk weekly to his cousin who lives near Agen and whom he regards as a sister having spent his earliest years with her. A formative influence in those early years was his French grandmother who made contributions to street people in need on her way to church. She was also a believer in giving to other worthy causes and impressed upon her grandson that, in the beginning, the act of giving is as important as the amount given. That seed planted in the child’s mind took root and evolved into Lee’s practice as a young man giving what he could to his alma maters then grew to include other causes and eventually blossomed into the Patrick Lee Foundation. His philanthropic credo is expressed in myriad ways from financial contributions and volunteer service for a wide range of causes locally and nationally to whatever advice, networking, and support he can provide for Lee Foundation scholars as they embark upon their own careers. So strongly does he believe in the value of giving not just to the recipient but to the giver that he incorporates it into the culture of his scholarship grants and encourages recipients to contribute to worthy causes by starting with even small amounts of money (he often suggests to their alma mater) to discover the life-enriching joy of giving.

Recently returned from an international trip with his grandchildren, he shared a moment when he was walking by a poor person asking for money in Greece and put several drachmas in the man’s hand. Lee confessed he finds it nearly impossible to walk by someone in need and not respond. It would be easy to judge the wealthy for giving to the poor what is to them literally pocket change–as John D. Rockefeller, Sr. was criticized, by some, for giving dimes to children on the streets of Manhattan. Yet, interestingly, Rockefeller, similarly to Lee, learned the importance of the simple act of giving as a child from his elders’ example. The enormous good to society and the world generated by Rockefeller philanthropy would be hard to overestimate. Not often recognized is that philanthropy for wealthy persons becomes more difficult the greater the resources are to share. Indeed, Patrick Lee cannot distribute his philanthropic wealth by himself. Done responsibly, it requires an incorporated foundation, a dedicated staff, immense data gathering and analysis, selection and recruitment of partner agencies and institutions, a committed and diverse board of directors, and the personal attention and almost daily decision-making of the donor. In other words, philanthropy for wealthy individuals and families takes more than the decision to give money away by writing checks or putting pocket change into the hands of street people. Philanthropic vision is rooted in a deep desire to make a difference in some select, defined areas of need and is sustained by disciplined business acumen and decision-making.

Lee seems never to have forgotten his own experience of being in need and benefitting from others’ generosity. Though not a family of poverty, he and his mother had limited means after his father’s death but enjoyed a loving home provided by his French relatives. Upon returning to the United States to begin school, Lee attended Creighton Prep, Omaha’s prestigious Jesuit secondary school, then attended the Jesuit run St. Louis University through a scholarship fund for children of war casualties. Giving is a core value of Patrick Lee from his earliest days to the present and represents a lifetime achievement equal to, if not greater than, the patents he secured and impact his companies had in the aeronautical industry.

Those early years of losing a father and living with relatives left an indelible mark on Lee’s memory. He still associates crossing the Atlantic at age seven to return to the United States after the war with the disruption and travail he and his mother experienced when his father was killed. “War is hell and can affect you for the rest of your life,” he admits, not elaborating on the hardship. There was, however, a Nor’easter he vividly recalls that their ship encountered on its voyage to New York from La Havre during which Lee lost his balance and fell down a flight of steps. That event pulled from his childhood is perhaps a metaphor for the storms he and his mother faced as a war widow and “war orphan” as children of service members killed in combat were called.

Lee’s education at Creighton Prep and St. Louis University’s Parks College of Engineering enabled his growth and development into adulthood and laid the foundation for his business success. In Lee’s pantheon of requirements for a successful life, not surprisingly, is a formal education. Hence, the primary mission of his foundation is scholarships for higher education. As an engineer deeply committed to American democracy and free enterprise and our role in the world, he understands the critical need, if the nation is to keep its technological advantage, to produce new engineers and increase the number of those entering STEM professions. The other major life event that shaped the mission of the Lee Foundation was his older son’s diagnosis of schizophrenia and the family’s search for mental health services and support. At that time–the early 70s–such help was limited and not easily found, especially in a world where mental illness was feared and misunderstood. Still, the Lee family rallied around Pat and enabled him to live with quality of life. Sadly, early death, often associated with schizophrenia, took Pat when he was in his 50s but Lee, his wife Cynthia, and Lee’s children continued to work to strengthen the mental health services of Western New York. They worked to solve a profoundly complex public health problem by helping to find and fund the best possible solutions through the support of the foundation. From the beginning, scholarships for those pursuing careers in nursing, psychiatry, psychology, and counseling as well as institutional grants have been awarded to improve and expand the region’s mental health network. In addition to program grants, the Lee Foundation, in partnership with twelve colleges and universities, awards over 125 scholarships annually for mental health, engineering, and STEM professions and has funded 466 students in these fields of study since 2007.

The other contributor to Lee’s personal development and success that should not be underestimated is the work he did each summer as a farm hand. “I was shipped out every summer for five dollars a day and room and board, on nearby farms,” he explains. “Later, when I was older, a friend and I had joint ownership of a used car and followed the wheat harvest north from Nebraska to Minnesota for $10 a day which was a lot of money back then.” Asked if it was hard work, Lee breaks into a subtle smile and replies, “It depends how you define ‘hard work.’” Questioned about what he learned from those long, hard days harvesting wheat, he describes a photograph acquired years ago of a dilapidated barn against a barren rural landscape. The picture has hung in offices Lee has occupied from the beginning and is now on the wall of his modest office at the Foundation. “When I got it,” he said, “it reminded me–and still does–of where I would end up without an education.” The education Lee is referring to is the formal education he received in high school and college. But clearly those summers of his youth when he worked and lived on Midwestern farms helped shape the values and bestowed the practical wisdom that formed him as a person and business leader.

Emerson would agree: “The farm is the right school,” he writes. “The reason of my deep respect for the farmer is that he is a realist and not a dictionary. The farm is a piece of the world… The farm, by training the physical, rectifies and invigorates the metaphysical and moral nature.” Tempered by the vicissitudes of weather, health, and the marketplace Lee understood first-hand the risks and rewards of hard physical labor that cultivated both a resilience and a pragmatism that learns from setbacks and moves forward to seek better and more efficient ways to expend energy and resources.

Coda

“As fast as you conform your life to the pure idea in your mind, that will unfold its great proportions.”

When I asked what motivated him in his early 20s to start his own company Lee said, “You’re the only one holding yourself back. The goal of a vocation is to find satisfaction, even joy in using your skills toward a larger end.” His quick response to my question revealed an existential truth of taking full responsibility for finding one’s path and purpose in life. It is a fundamental truth Emerson points to again and again.

In hindsight, Lee made what he accomplished almost look easy. But the fact is, just a few years out of college, he left the firm that brought him to Western New York and the security it provided to start his own business. “We didn’t have much,” he recalls, “but we generated enough revenue out of the shop until we had our first patent, then got a foothold in the industry and we were off and running.”

His consistent use of the word “we” when discussing his business and philanthropy conveys his belief that it wasn’t just him, but those he hired as staff and those he carefully selected and recruited to serve on his boards who get the credit. One board member wondered if Lee realizes how special he is. “He certainly knows he’s intelligent,” she said, “but the gifts he brings to management and leadership are one of a kind. He has a very sturdy ego, you could say he is self-possessed,” she continued. “You have to be, to succeed to the extent he has. But he almost takes his brilliance for granted, as nothing out of the ordinary for any competent leader. The result is genuine humility.”

When Lee started his business, he named the company Integrated Dynamics Incorporated (IDI). But the first licensing company abroad of IDI products was a European firm, yet they had a problem with such a lengthy name and proposed a new name: Enidine–En representing “energy” and dine, a measurement of force required to accelerate mass. When he put the name change to his employees for a vote they chose the new name for the company.

Enidine: energy, the measurement of force needed to accelerate mass–virtual synonyms for Emerson’s “Will to power” and “Darting to an aim.” A fitting name for a firm founded and run by a force of nature himself, an Emersonian Individual, a true American story.

in print